Crawford Lake in Milton, Ontario, is the recommended site to geologically define the start of the Anthropocene. (Credit: Cale Gushulak)

Crawford Lake tells a story

Evidence that humans impact the environment is widely available, from deforested areas to extinct species and increased climate catastrophes. But is human pressure so dramatic that it merits a new chapter in Earth’s history? Many scientists believe so, and they are closing in on a place on the planet where they say the start of the Anthropocene epoch can clearly be seen and studied.

The Anthropocene epoch is believed to have begun in the middle of the 20th century, when human activities became the dominant force governing the planet’s climate, continents, and oceans. Its start marks the end of the Holocene geological epoch, which began as the last ice age retreated, about 11,700 years ago.

In 2009, the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) established the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) to evaluate locations around the globe that could provide a physical reference of the new geological unit of time, clearly showing changes based on human impact and interaction. From Antarctica to Canada, Europe, China, and Australia, 12 different candidate locations were proposed and evaluated, including ice sheets, ocean beds, lake sediments, and coral reefs.

Dr. Brian Cumming’s team contributed to the precision and accuracy of dating processes for the samples extracted from Crawford Lake and understanding changes in important biological indicators of environmental change. (Credit: © Stephany Hildebrand 2020)

Today, the group officially announced their recommendation: Crawford Lake, in Milton, Ontario, just northwest of Toronto.

An interdisciplinary crew of dozens of scientists led by Francine McCarthy (Brock University) came together to champion Crawford Lake’s candidature. Brian Cumming, a Professor of Paleolimnology and Aquatic Ecology at Queen’s, was part of that effort.

"Having the Anthropocene move from an undefined period used in popular culture, and by many scientists, to a formal geological epoch is important because it recognizes a fundamental reality: humans have changed Earth to such an extent that it is now officially recognized in the geological record," he says.

The idea of the Anthropocene is not new – a century ago, Russian geologist Aleksei Pavlov proposed we were living an anthropogenic period. But it wasn’t until the early 2000's that the term Anthropocene became more popular, after the release of a book of the same title by the late atmospheric science expert Paul Crutzen and biologist Eugene Stoermer.

While many geologists agree that this new geological epoch has begun, they are yet to find consensus on how to accurately define the start of the Anthropocene. This is where Crawford Lake comes in, with the hope that scientists will be able to see where to set a "golden spike" to mark its start.

Muddy soil for a clear record

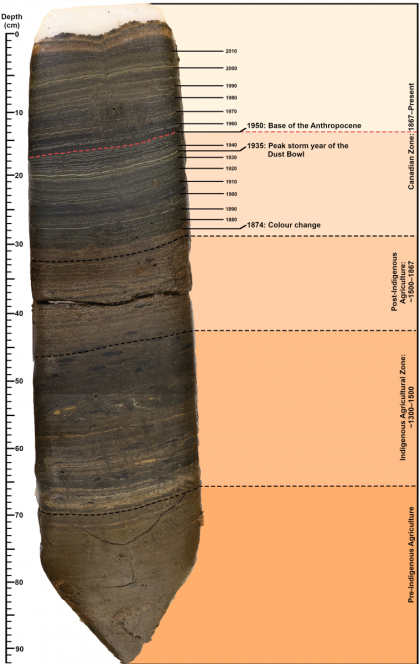

Crawford Lake is small and relatively deep for its size. Its storytelling power comes from its depths, where the layered sediments record changes on the physical, chemical, and biological remains that have accumulated over time. The impressively well-defined mud layers contain a record of everything that has encountered the water and settled at the bottom. These layers can be read like tree rings, revealing a detailed environmental record for over a thousand years.

To access these records, scientists need to extract samples from the lake’s bottom. They do this with the help of many different coring devices, including a frozen aluminum tool that is lowered to the murky depths. This tool dips into the mud and freezes a sample, revealing the striped print of the sediment layers dating back hundreds of years.

Analysis of these cores have shown, for example, evidence from crops cultivated by Indigenous communities, ashes produced by burning coal and oil, and radioactive plutonium generated by nuclear weapons’ tests. Combined, these proxies suggest a tipping point when the anthropogenic pressure on the environment became overwhelming – somewhere around 1950, when the world saw a remarkable acceleration of resource use and population growth.

This is not the first time that Queen's researchers have participated in defining geological landmarks. Guy Narbonne (Geological Sciences and Geological Engineering) played a key role in defining the international standard for the Cambrian Period (approximately 538.8 to 485.4 million years ago) and in the designation of the Ediacaran Period (approximately 635-538.8 million years ago).

Algae and environmental change

The frozen core extracted from the bottom of the lake reveals layers of accumulated sediment. The layers can be read like tree rings and represent a record of hundreds of years. (Credit: Patterson Lab, Carleton University)

For decades, Queen’s biology experts, members of the Paleoecological Environmental Assessment and Research Laboratory (PEARL), have been investigating how ecological and environmental changes leave their mark on lakes like Crawford. One of their main contributions for helping to define the Anthropocene "golden spike" was assessing the presence of certain types of algae in the muddy layers that have rested on the bottom of Crawford Lake for the past 200 years.

Dr. Cumming and his students found that the algae preserved in dated sediments from Crawford Lake changed dramatically over time. These changes can be tied to environmental factors like agriculture, local forest harvesting, industrial pollution, and other human activities.

"The history of Crawford Lake shows a progression from local changes impacting the lake, such as impact on the watershed, including the clearance of forests, to regional changes associated with industrialization such as acid deposition, and climate change," explains Dr. Cumming. "Changes were most rapid post-Second World War, supporting this site as a strong candidate site for marking the start of the Anthropocene."

The area surrounding Crawford Lake has been occupied for a long time: for a few decades now, scientists have been investigating traces of human presence in the area, and evidence points to ongoing horticultural activities from the 13th to the 15th centuries.

Today, the people thought to be the descendants of the Indigenous group who inhabited the region in the past are the Wendat. Representatives of this community accompanied the fieldwork carried out in 2023 and conducted protocols including discussion, smudging and a ceremony before the coring activities.

"It is very valuable to have Elders with us during field work to help ensure that everyone is keeping a good mind," says Monica Garvie, an Anishinaabe woman and PEARL PhD candidate that helped the research team liaise with the Wendat community. "They also provided support for the team during coring, for example, if anyone got tired or too exhausted, they could speak with the elders to receive some encouragement."

Next steps

Fieldwork expedition to Crawford Lake in Winter 2022. (Credit: Monica Garvie)

While the effects of human pressure on the environment are no surprise, formal geological recognition might support the research community in advocating for conservation of Crawford and other lakes.

"An increasing number of scientists have been speaking out about threats to our ecosystems, biodiversity and the ongoing climate crisis and other environmental issues. We hope the formal recognition of the Anthropocene promotes humanity to recognize the magnitude of human activities on our planet, and results in a new urgency for positive change in the way we treat our planet," says Dr. Cumming.

Now it’s over to the International Commission on Stratigraphy, who will evaluate the final recommendation to ratify the end of the Holocene, marking the start of the Anthropocene epoch.

If the geological time scale can be compared to a series of books that tell the story of our planet, the Anthropocene is the latest new release. Its first chapter – the Crawfordian Age – describes a critical moment in our shared environmental history, one that Earth and humanity will write side by side.

This story was originally published on the Queen's Gazette.