January 21, 2020

by Louisa Simmons

Editor's note: This piece is the first instalment in our series Words of War: Canadian English in the First World War.

If you were to stand in one of the many winding trenches occupied by the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the First World War, not only would you be ankle-deep in mud and shell casings, but you would likely hear soldiers speaking in a string of words that made no sense to you. That’s because the Canadian soldiers who fought overseas from 1914-1918 developed a kind of code for communicating made up of unique slang terms and expletives that described trench life, weaponry, and the general conditions of war.

______________________________________________________________________________

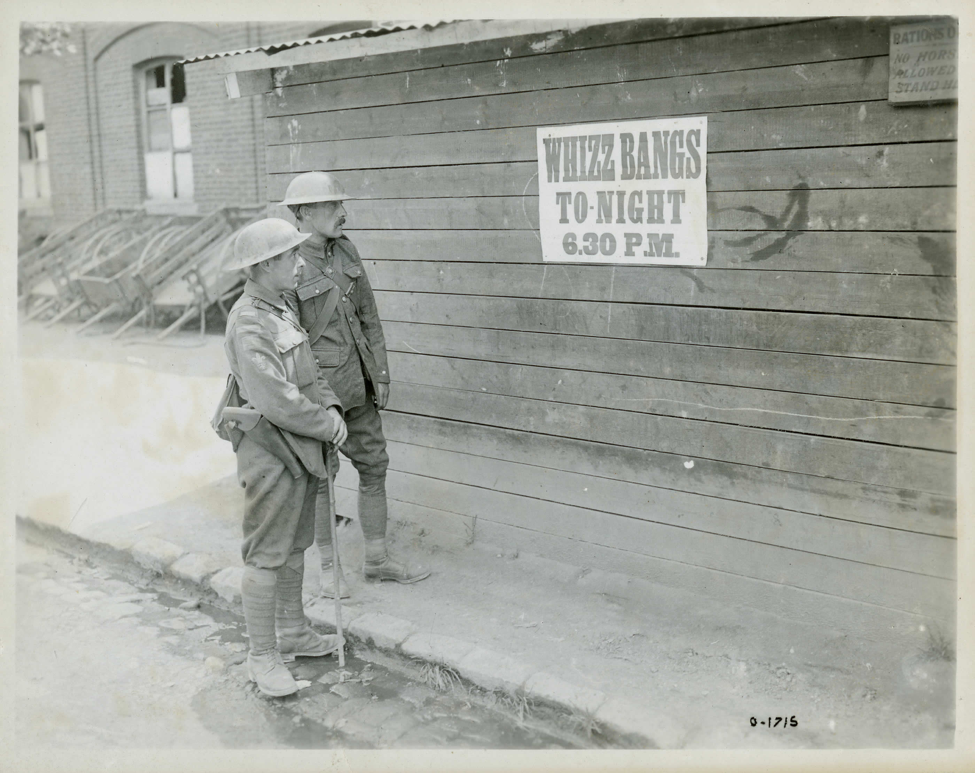

Canadian soldiers looking at a sign for an upcoming performance of an entertainment troupe

named "Whizz Bangs" after the common slang word for a flying shell.

Photo: Canadian War Museum

__________________________________________________________________________________

One of the most plentiful categories of slang terms to become part of Canadian English during this time is in relation to weaponry. Canadian military historian Tim Cook argues that “in a response to the industrialized nature of death, soldiers reacted to the impersonal killing devices of shells and bullets by drawing them back to the knowable and understandable. The rocketing shells overhead were likened to trains running or trucks driving out of control.”1 It makes sense then, that soldiers who were constantly threatened by weapons firing around them would create humorous nicknames as a way to cope with the danger they experienced.

As a result, a threat like an incoming shell would be downplayed by referring to it as a whizz-bang. These nicknames were not created arbitrarily, instead they were often coined because of some common observation soldiers made about the weapons. For example, Canadian Private Donald Fraser wrote that “Whiz-bang is the name given to a light shell of high velocity and trajectory. It is practically on the top of you as soon as you hear the report of the gun…First you hear the whiz and almost simultaneously comes the bang, then a metallic singing in the air as the pieces of Shrapnel fly through the space.”2

__________________________________________________________________________

A short entry in the Canadian trench newspaper "The Listening Post" describing the many sounds, like "whizz bang" that soldiers heard daily. Trench papers were written by, and distributed for, soldiers on the front. Photo: The Listening Post, No. 27, August 10, 1917 p. 21

__________________________________________________________________________

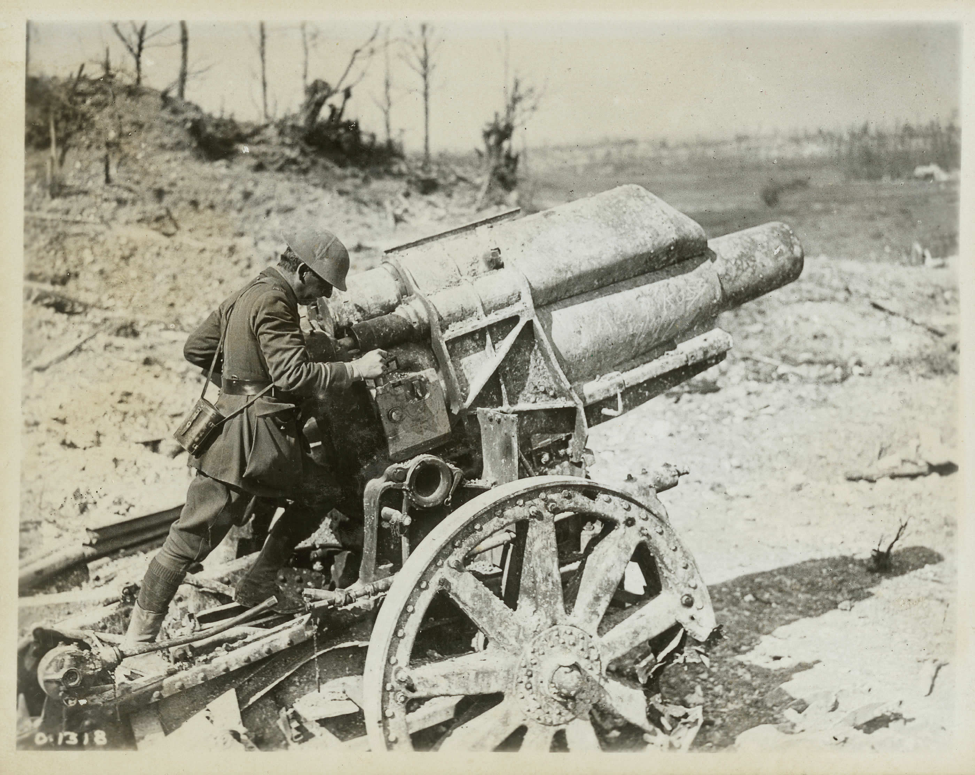

Nicknames describing the sounds certain weapons made were just one category of slang. In fact, one of the most common methods for nicknaming guns and shells was to give them human-like names. So, a 42cm German howitzer gun became a Big Bertha. A close relative was the Bouncing Bertha, jokingly named because the last thing the massive shell would ever do was bounce. Minnie was the nickname for a short-range mortar officially known as a minenwerfer (although they were also often called flying pigs, toffee apples and plum puddings). Some shells were named after celebrities: the Jack Johnson was a large 15cm German artillery shell named after the famous American boxer.3

________________________________________________________________________________

A Canadian officer inspecting a recently captured German gun. Photo: Canadian War Museum. George Metcalfe Archival Collection.

________________________________________________________________________________

Another way that soldiers referred to weapons was by giving them nicknames based on their similarity to everyday objects. Different versions of the grenade – a small bomb usually launched from a handle during the First World War – received colourful names. A hair brush was an early British grenade shaped like…well, a hairbrush. A potato masher was the German counterpart, nicknamed as such because of the long wooden handle that resembled the kitchen tool. There were also crab grenades and toads.4

Bayonets – the long knives attached to the ends of rifles which could be used in combat – were the subject of many humorous slang terms. Because it was functionally a knife, a bayonet was commonly used as a cooking tool in the trenches, thus giving it nicknames such as tin opener, toasting fork, or tooth-pick. Outside of the realm of cooking, it was also known as a cat-stabber and a pin or winkle pin. It is the soldier’s trivialization of these dangerous weapons which military scholar John Brophy argues “may well have reduced the emotional distress caused by fear, and aided him, after the experience, to pick his uncertain way back to sanity again.”5

The slang adopted by soldiers to describe weaponry in the First World War was extensive. While most of these terms are not in use today, they give us a window into the lives and experiences of the soldiers who used them, and they illustrate an important period in the history of Canadian English.

____________________

1 Cook, Tim. 2013. "Fighting Words: Canadian Soldiers’ Slang and Swearing in the Great War." War in History, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 332.

2 Reginald H. Roy, ed., The Journal of Private Fraser: 1914–1918, Canadian Expeditionary Force. Ottawa: CEF Books, pp. 36–7.

3 Pegler, Martin. 2014. Soldiers’ Songs and Slang of the Great War. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

4 Ibid

5 Brophy, John, and Eric Partridge. 2008. Dictionary of Tommies’ Songs and Slang 1914-1918. South Yorkshire: Frontline Books.

___________________

More weaponry slang!

Many of the terms mentioned in this article were sourced from Martin Pegler’s expertly written Soldiers Songs and Slang of the Great War, and John Brophy and Eric Patridge’s formative Dictionary of Tommies’ Songs and Slang. Below is a selection of other interesting slang words pertaining to First World War weaponry.

Asiatic Annie

A large-calibre Turkish gun used in the conflict at Gallipoli in 1915.

BSA

Birmingham Small Arms was a large firearms manufacturer that also produced motorcycles for the war. The vehicles became known for having poor suspension and BSA became colloquially known to mean “bloody sore arse.”

butt-notcher

A term for a sniper, coming from the habit of some soldiers to notch the stock of their gun for each kill. This was widely discouraged by the army as it meant a captured sniper would likely meet immediate death.

carpet slipper

A large and heavy shell passing high above a soldier, nicknamed such for the sound it made as it flew overhead.

crappo

A French trench mortar. The French term is “une crapaud” so this nickname was a bastardization of the word into an English equivalent.

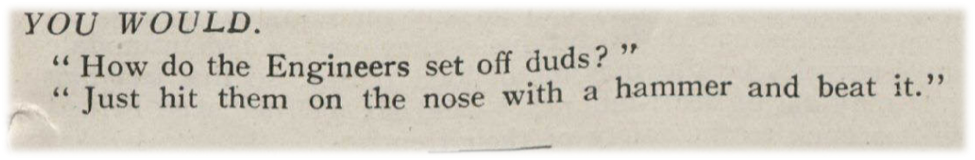

dud

A shell that does not explode.

A short entry in "The Listening Post" using the term "dud". Photo: The Listening Post, No. 27, August 10, 1917, p. 21.

Emma

A German nickname for a large artillery gun.

flaming onions

A German 37mm gun that had a tracer compound which could track the projectile, nicknamed as such because it fired bullets upwards in long lines.

grass cutters

Aerial bombs which were small in size and created splinters that scattered upon explosion.

hate

A heavy bombardment of shells. It was named after the famous German propaganda song Hymn of Hate. Daily German bombardments were therefore nicknamed the daily hate or morning hate.

iron foundry

A term for heavy shelling.

lebel ma’m’selle

A name for the French Lebel M.1893 rifle. The term arose from a bastardization of the French saying “la belle mademoiselle.”

mouth organ

A name for the Stokes mortar bomb, likely due to the wailing noise which the shell made when flying overhead.

nuts

A term for bullets, influenced by the tendency of French soldiers to refer to their own bullets as different types of nuts: “chatâignes, pralines, pruneaux", etc.

potato digger

The colt machine gun. The name comes from the operating arm, which moved on an angle back and forth as the gun fired, mimicking the motion of digging up potatoes.

rum jar

A name for a German model trench mortar which resembled the stoneware rum jar issued to British and Canadian soldiers.

stop

To be hit with a bullet or shrapnel shell. Pegler uses the example of “Harry’s just stopped one.”

Tickler’s artillery

A type of homemade grenade which was fashioned out of tins of Tickler’s jam (the most widely issued jam to British and Canadian soldiers).

Wipers express

A huge 42cm German shell used during the Second Batlle of Ypres (21 April – 25 May 1915). Ypres was often called Wipers by English-speaking soldiers who could not properly pronounce it.