Date: May 30, 2012 | Category: Guest Column

Author: Nicole Rosen

As a linguist interested in language on the Prairies, I have recently begun collecting a Southern Alberta Corpus of English (SACE) which stratifies speakers according to the usual social variables: age, sex, and socioeconomic status, but which adds two dimensions which are not always present in other corpora: rurality and religion. Rural Canadian English has been sorely underrepresented in the study of Canadian English, generally, though it is likely one of the most salient varieties of Canadian English. There has not been much discussion of religion as a variable in Canada either, though there have been a few recent papers discussing Mormonism (Baker & Bowie 2010, Sykes 2010) or Judaism (Benore 2011) as a variable in the U.S. Getting back to Canada, in 1998, Marjory Meechan published a paper on the "American" variety of English in Lethbridge, Alberta, spoken by Latter-Day Saints (referred to generally as the Mormons, or LDS). This led me to include LDS as a variable in the development of SACE. Why would LDS members have their own variety of English, you might ask? Well, it is likely based on at least two things: immigration history and tight social networks.

Starting in 1887, as tensions between the United States government and Church of the Latter-Day Saints became more and more strained, a large number of LDS began to migrate north from Utah into Southern Alberta, seeking a friendlier government and religious freedom (Palmer 1972). By 1911, LDS in southern Alberta had established 18 communities, and ten thousand members of the church lived in the region. This group continues to be important in the area today. According to the 2001 Canadian Census, 49.7% of Canada?s entire LDS population is situated in Alberta. In the 2001 Canadian Census, 8.5% of Lethbridge and 13% of Taber self-identified as LDS, far higher than the national rate of .3% and even the provincial rate of 1.7%. Though there are no public documents giving us numbers of people practicing different religions in the smaller municipalities in Southern Alberta, locals know which towns are "Mormon towns." They include towns such as Magrath, Raymond, Sterling, Cardston, etc. We can estimate LDS population by the number of "stakes" or "wards", administrative units composed of multiple congregations. A ward is composed of 200-500 people in a geographical area, and a stake is generally made up of at least 5-8 wards, and equal to approximately 3000 people. There are at least 9 stakes south of Calgary, and six in Calgary itself. Note that Cardston, a town with 3500, has two stakes (which includes the district surrounding the town), and so we can extrapolate from that an extremely high LDS population. Indeed, Cardston was the initial settlement in 1887 by LDS settlers from Utah, and boasts the oldest Mormon temple outside the United States.

Despite participating fully in Canadian society, attending public schools and universities and working ?in town?, Meechan (1998) describes the LDS community as having ?largely remained a cohesive group reinforced by the social activities associated with their church?. It is true that they form a tightly knit network within the region.

LDS members interact intensely with one another, establishing a community of their own. There are generally three hours of church services on Sundays; Monday is set aside for family night; there are singles activities during the week on Tuesday or Wednesday; and most people have ?callings? which are responsibilities/jobs within the church that keep one busy a number of times a month. Saturdays are spent preparing for Sunday services. High school students also attend Seminary for an hour before school during the week. In and around Cardston, there is an additional factor of the Temple. Practicing members are expected to attend the temple regularly, and this attendance maintains the tight-knit feel between those who attend regularly. There is a high expectation to always be eligible to go to the temple and to attend as much as possible.

Cardston-area LDS members are thus an excellent example of a tightly-knit social network in the sense of Milroy & Milroy (1992):

|

?a close-knit, territorially based network functions as a conservative force, resisting pressures for change originating from outside the network?Close-knit networks, which vary in the extent to which they approximate to an idealized maximally dense and multiplex network, have the capacity to maintain and even enforce local conventions and norms - including linguistic norms - and can provide a means of opposing dominant institutional values and standardized linguistic norms. |

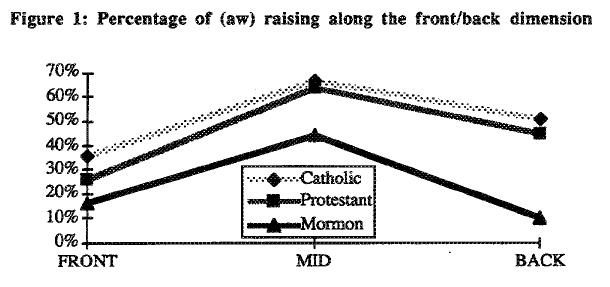

Meechan investigated this question in Lethbridge, Alberta, and wrote a dissertation entitled The Mormon Drawl: Religious Ethnicity and Phonological Variation (1999) which showed that LDS in Lethbridge are less likely to participate in Canadian Raising than Protestants or Catholics.

(Meechan 1998:43)

This research shows quite clearly that there is a division along religious lines in Southern Alberta. What is more, my own research is finding similar divisions elsewhere in the system.

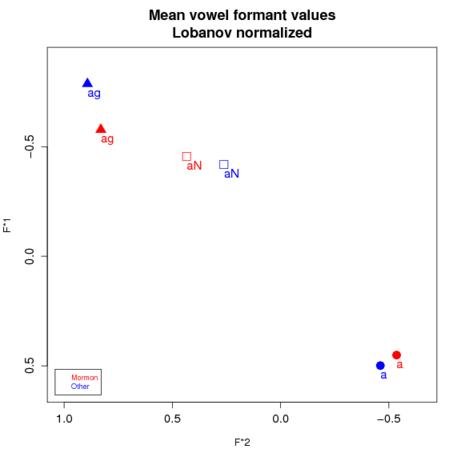

Boberg (2008, 2010) shows that /æ/-raising before /g/ is a regional indicator for the Prairies. That is, /æ/ raises more before /g/ in the Prairies than elsewhere. (Incidentally, Boberg shows that/æ/ raises more before nasals in Ontario than elsewhere.) We are undertaking research in my lab to find out whether this linguistic feature of Prairie Canada is robust within the LDS in Southern Alberta as well. If the LDS are a closely-knit network resisting Canadian linguistic change such as Canadian Raising, we would expect this resistance to occur elsewhere in the phonological system as well. Our findings so far are quite interesting. As it happens, /æ/-raising before /g/ is indeed much more robust among rural non-LDS than among rural LDS, at a statistically significant level. The vowel space is plotted as below.

As we can see from the vowel plot, /æg/ is higher for all speakers than /æ/ before nasals or before other segments, but the non-Mormon speakers are significantly higher than Mormons.

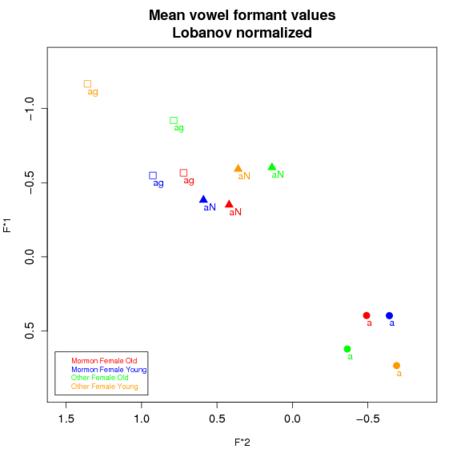

Because this is a shift in progress, it is useful to compare older speakers with younger speakers. What is especially interesting when we look at the women aligned with age, is that we find, as expected, young women at the forefront of the change, but for the non-LDS group only. Young Mormon women (in blue) pattern very closely with the older Mormon women (in red).

Conversely, the young non-LDS women (in yellow) have much a higher /æg/ vowel than both the older non-LDS women (in green) and the LDS young women (again, in blue). In fact, even the older non-LDS women raise more than younger LDS women, suggesting that the LDS group is very resistant to this Canadian change. Put another way, the change is further along among the older generation of Southern Albertans than with the younger generation of LDS Southern Albertans. This is not what we would normally expect, as young women are normally the leaders of these changes. However, it does show that the LDS do not appear to be moving at the same pace as the other speakers in the region with respect to this highly regional variable.

The question remains: what are the reasons behind these differences? Some have suggested that Alberta LDS speakers are more influenced by Utah LDS than by their Canadian neighbours, and they are adopting Utah LDS speech (Meechan 1999). It is true that there is a lot of back-and-forth travel between the two groups. Or is it simply that they are slower to adopt the Canadian changes due to their close-knit community which is in less daily contact with non-LDS? I believe it is more likely the latter than the former, but this is research in progress and I don?t want to give it all away too soon.

References

Baker, Wendy and David Bowie (2010) Religious affiliation as a correlate of linguistic behavior. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 15.2, Article 2.

Benor, Sarah Bunin. 2011. Mensch, bentsh, and balagan: Variation in the American Jewish linguistic repertoire. Language & Communication 31. 141?154.

Boberg, Charles (2008) Regional phonetic differentiation in standard canadian English. Journal of English Linguistics36, 129-154.

Meechan, Marjory (1999) The Mormon Drawl: Religious ethnicity and phonological variation. PhD Dissertation. University of Ottawa.

Meechan, M. (1998) I guess we have Mormon Language: American English in a Canadian Setting. Cahiers Linguistiques D?Ottawa26, 39-54.

Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy (1992) Social network and social class: Toward an integrated sociolinguistic model. Language in Society21, 1-26.

Palmer, Howard (1972) Land of the Second Chance: A History of Ethnic Groups in Southern Alberta. Lethbridge, Alberta: The Lethbridge Herald.

Statistics Canada (2001) Religion by immigrant status and period of immigration. Retrieved on May 13, 2012 from http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/products/highlight/Religion/CSD_Menu2.cfm?Lang=E&Code=48

Sykes, Robert D. (2010) A Sociophonetic Study of (ai) in Utah English. M.A. Thesis, University of Utah Department of Linguistics. http://www.robertdsykes.org/public/thesis.pdf