When she decided to pursue a career in art conservation, Patricia Smithen had no idea that it would one day mean overseeing the care and feeding of a room full of butterflies at the Tate Modern, one of the world’s most esteemed contemporary art galleries. She also had no idea that she would one day find herself teaching at Queen’s in the very department where she had received her own training 25 years earlier.

Smithen, who has also worked as a paintings conservator at the Canadian Conservation Institute, the Detroit Institute of Arts and in private practice, landed at the Tate in London, England in 1999. She then worked her way up from Conservator of Modern and Contemporary Paintings to the Head of Conservation, Programme, where she was responsible for the Tate Conservation strategy for exhibitions and displays, and the care of the institution’s 60,000 works of art. During that time, she studied and worked on priceless paintings by Salvador Dali and Mark Rothko, among many others.

But it was during was a 2012 retrospective of work by the British artist Damien Hirst – a controversial superstar known for things like preserving animals in formaldehyde and encrusting skulls in diamonds – that Smithen found herself responsible for the literal care and feeding of a dynamic work called In and Out of Love (White Paintings and Live Butterflies). Over the course of the exhibition, butterflies would emerge from cocoons affixed to white canvases in a humid room, leaving traces of their existences on the canvas. They would then fly around the room.

“It was one of the craziest things I have ever worked on,” Smithen laughs, thinking back on the inherent conservation challenges. “The butterflies would vomit on the canvases. It would be everywhere. Do you document that? Are they considered paintings? And we had artworks from other museums on other side of the butterfly room, so we had to plan for butterflies escaping the room. But it was fun. So much fun.”

Ultimately, however, it was still the materiality of paint that had captured Smithen’s conservator heart. In 2015, she left her position at the Tate to pursue a PhD through the Courtauld Institute of Arts and Tate Gallery. Her area of research is the development and impact of artists’ acrylic paints in the United Kingdom, and she hopes to have her thesis completed by 2019.

Smithen was first drawn to contemporary art restoration because she was interested in the way artists apply paint in different ways. “I like the materiality of it,” she explains. “There aren’t always real images – it’s often just about the paint. The subject is the paint – and I find that fascinating.”

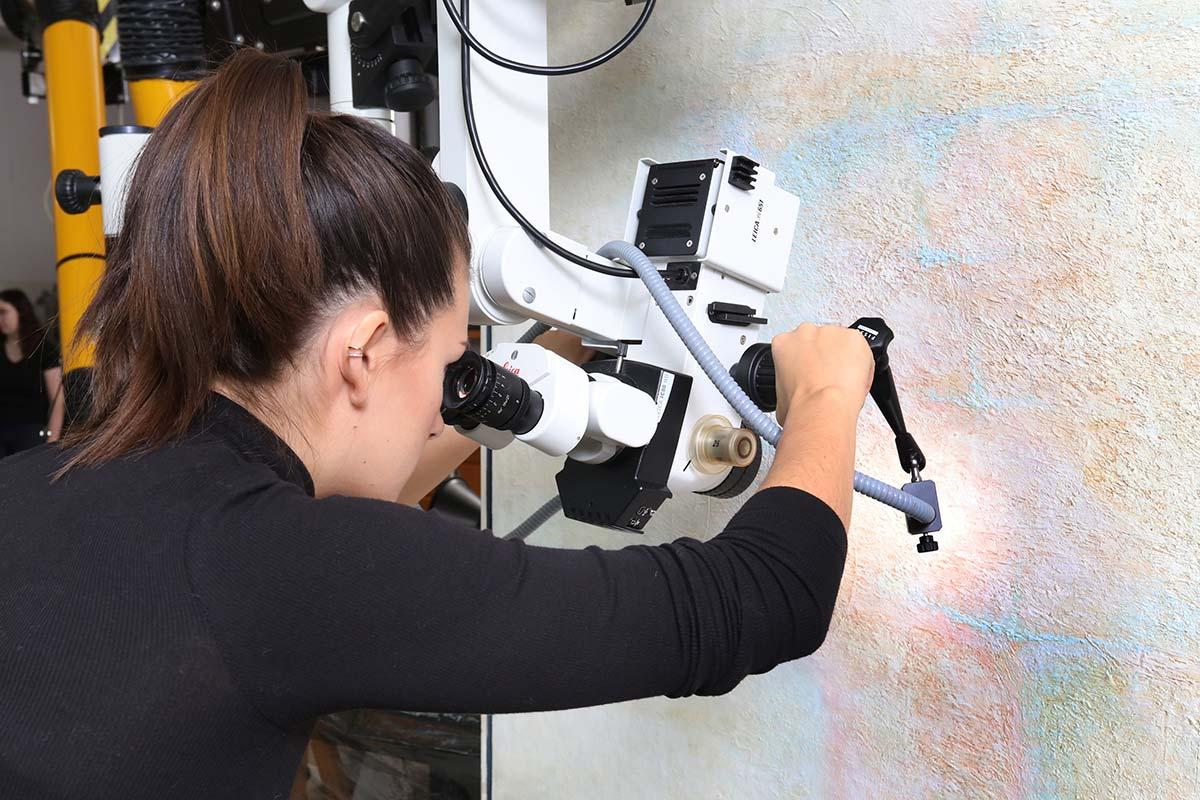

Since arriving at Queen’s as an assistant professor in Art Conservation, she has been able to share her passion for paint with her students in a program that sees her working closely with them on conservation challenges in the studio for at least four hours every afternoon. “Not only do you have to teach the hands-on skills and processes,” she says, “but you also have to teach the technical skills and ethical approaches which lift up into a professional qualification.”

Smithen is currently thrilled to be working with her students on restoring a number of important paintings by the late Canadian artist Graham Coughtry, some of which offer up challenging conservation problems. This includes a large-scale, genre-defying work on paper of an ethereal figure floating in a pinky-yellow void, which second year Master’s student Valerie Moscato has been tasked with restoring under Smithen’s supervision.

“They are really complicated works,” says Smithen, describing the artist’s category-defying habit of mixing early acrylic paints in with oils to change their consistency, making them a particular challenge to restore. “Our researchers and students are working on real paintings with real problems.” With the works on loan to the program from private collections, they also get work with real clients.

For Smithen, one of the challenges of working in conservation is staying on top of new techniques and emerging technologies borrowed from biology, geology and medicine. “Conservation is evolving quickly,” she says. “You have to keep up with the materials and processes to stay relevant and to keep your students employable.”

She is delighted to be working closely with the next generation of art conservators, sharing her years of experience in the field. “The students are so clever and dedicated and enthusiastic. It’s a pleasure to work with them.” She is also aware of the responsibility that comes with teaching as part of the only Master’s of Art Conservation program in Canada. “We are training the next generation of conservators for Canada. It’s a huge responsibility. We have to be good.”

![[paint photo by Bernard Clark]](https://www.queensu.ca/research/sites/default/files/assets/featured_story/BC%203686.jpg)