When is a work of art more than meets the eye?

Figuratively speaking, maybe always. But often this idea may also be literally true.

Take a painting. Beneath the surface could be a hidden kaleidoscope of pencil drawings, altered compositions, and brush strokes of abandoned bowls of fruit. When taken together, these undercover bits might reveal hints about an artist’s vision, evidence of damage and repair, and even clues to authenticity. In other words, answers to some of the most pressing questions posed by conservators and conservation scientists.

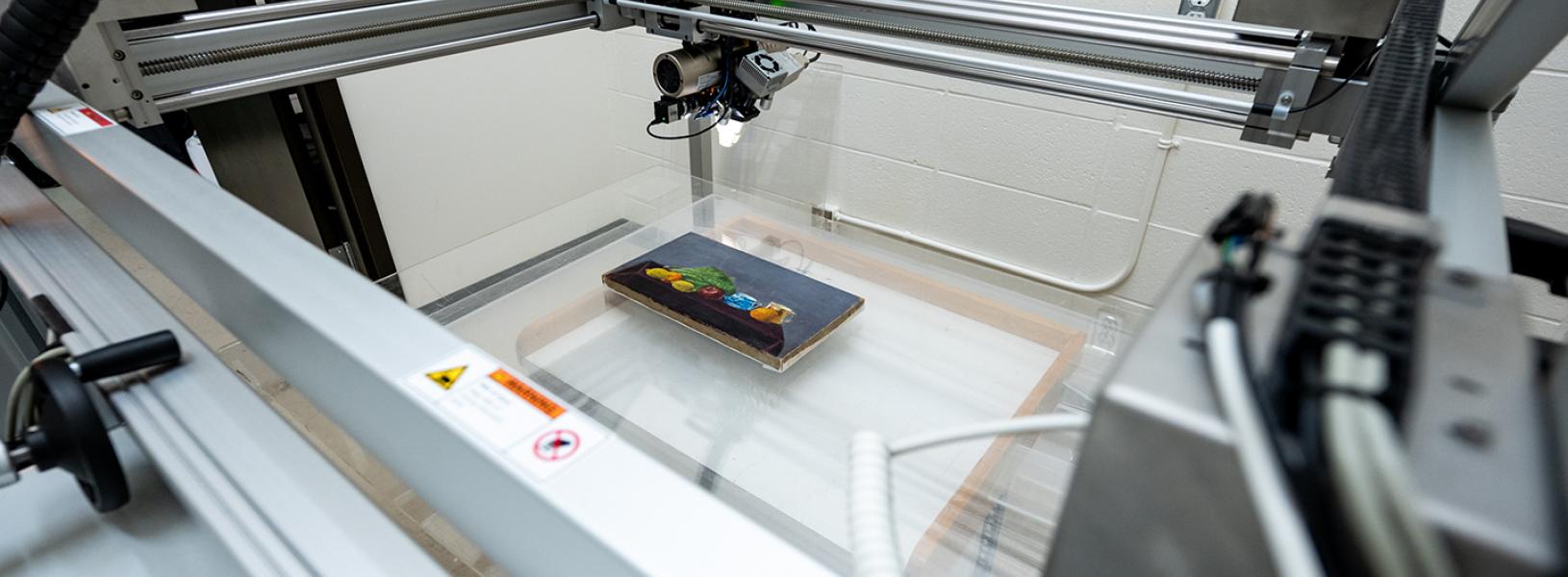

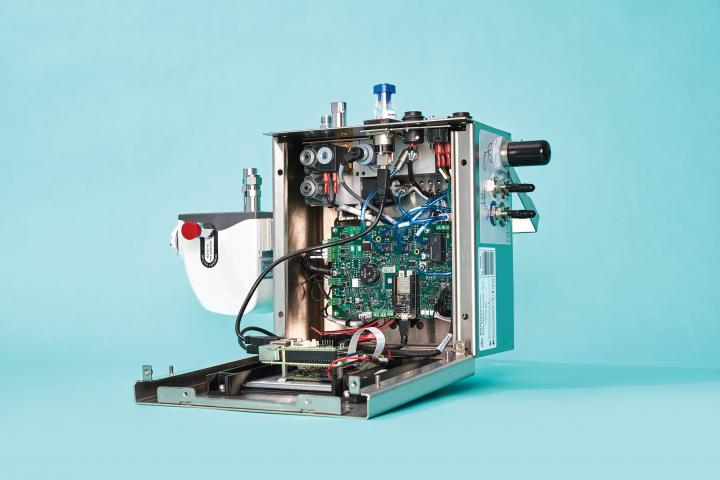

The problem, of course, is that those art conservators can’t actually see the buried bits with their own eyes. They also don’t know everything about what they can see, including what a painting’s pigments are made of. They need sophisticated technologies to do all of this – such as the Bruker M6 Jetstream X-ray fluorescence scanner (a.k.a. the M6). It’s one of the most advanced tools for visualizing the chemistry of an entire artwork, and the Queen’s Department of Art History and Art Conservation acquired one in 2020 through a $1-million-plus donation from the Jarislowsky Foundation.

It’s the only M6 in Canada, which makes it invaluable not only to Queen’s and Canadian art but to every student who uses it, says Patricia Smithen, Associate Professor of Paintings Conservation. “It’s so powerful,” she says. “It gives us so much information that other techniques just can’t.”

The M6 is so powerful because it can scan a whole artwork. Other X-ray tools can reveal information about a single spot, but the M6 collects data at thousands of spots. After several hours of scanning, it produces a map of all the chemical elements in the work, which in turn can direct researchers to the artist’s choices. Last year, for instance, a map of a Rembrandt oil painting at Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Head of an Old Man in a Cap, helped researchers identify the pigments Rembrandt used, as well as the alterations he made.

The M6 is a “wonderful advancement in the field,” says Aaron Shugar, Bader Chair in Art Conservation. “The number of new questions that come about when we can look at the chemistry of an entire artifact or painting as a whole as opposed to individual tiny spots is groundbreaking. So, Queen’s is lucky to have this. It creates fantastic opportunities for our students.”