Canadian physicists, led by Nobel laureate Dr. Art McDonald of Queen’s University, are playing a central part in the lightning-fast development of a new ventilator design that’s meant to reduce the global shortage of these devices during the pandemic.

Particle physicists from nine countries – mainly Canada, the United States, and Italy – brought the Mechanical Ventilator Milano (MVM) from the early-concept stage to Health Canada authorization in six months last year.

There has been a supply problem: Manufacturers are making ventilators, but many of them “have so many bells and whistles and are applicable to a much broader suite of things. That helps drive up the price – and also the time it takes to build them,” says Dr. Tony Noble, scientific director of Queen’s Arthur B. McDonald Institute, which studies astroparticle physics. He said the Milano model is like the Second World War jeep: simple and designed to be mass-produced.

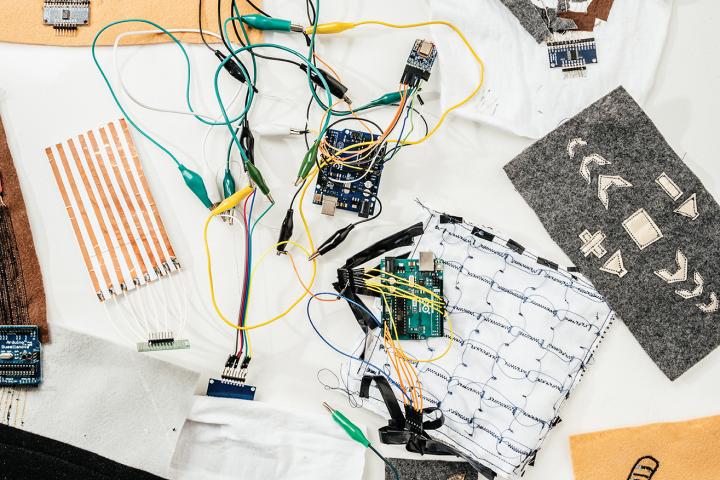

The new device was inspired by the Manley ventilator of 1961. The MVM is designed for large-scale production in a short time and at a limited cost, as it relies on off-the-shelf components readily available worldwide.

The first working MVM prototype was built just 10 days after someone suggested it, which is amazingly fast, Dr. McDonald says. There are now 6,000 MVMs in Ottawa ready for use here or for export to less developed countries.

Simple to operate: The ventilator needs only compressed medical air or oxygen and an electrical supply to power it; there’s no motor. Controls are simple: the MVM has two main modes – full ventilation for patients who can’t breathe at all or gentler breathing support. The big advantage is simplicity. “We have [about] 50 central components in the device,” Dr. McDonald says. Typical hospital ventilators “can have more than 1,000.” That means the MVM can be built quickly and in countries that are not industrial leaders.

“The new MVM has sensors and computer software to open and close valves as required for a number of circumstances.” says Dr. Noble. “For instance, the machine must react if a patient who wasn’t breathing on their own starts to breathe a little.” The ventilator recognizes such changes and reacts in a safe way.

Engineers tracked down parts that are available worldwide and designed the hardware based on that availability. Hospital doctors in Lombardy, a region of Italy with high rates of COVID-19 at the time, gave advice from the front lines on what they needed and tested prototypes beginning last April. (The device is named Milano after the capital of their region.)

“What really impressed me was the fact that the people who worked on the project pivoted quickly and enthusiastically from what they were normally doing. They were just so pleased to do something that might be of concrete assistance in the pandemic,” Dr. McDonald says.

MVM began as the brainchild of Cristian Galbiati of Princeton University, who was in Milan when the pandemic arrived. Besides Queen’s, Canadian groups involved include the Arthur B. McDonald Institute, Canadian Nuclear Laboratories, TRIUMF in British Columbia, and SNOLAB. In Canada, the device is built by Vexos Inc. of Markham.