The Master of Art Conservation program at Queen’s University is a small world that reaches around the world.

It’s Canada’s only graduate-level program in art conservation, and one of just five in North America. It produces only a dozen or so graduates per year, yet those relative few work around the world researching and conserving everything from Rembrandt paintings to baby mammoths.

“We have students working on all continents, in very prestigious institutions, as well as working privately,” says Rosaleen Hill, Co-director and Associate Professor of Paper, Photographic Materials, and New Media conservation. “It’s a small world, and it’s a very interconnected world.”

What’s not small is the range of objects that students work on, says Patricia Smithen, Co-Director and Associate Professor of Paintings Conservation. There are “Barbie dolls that had been used in museums as demonstrations for medical processes” and “3,000-year-old Egyptian mummy coffins,” as well as paintings, photographs, works on paper, and a seemingly boundless world of artifacts encountered in the program’s four specialist areas: conservation science; conservation treatment of paintings; works on paper/photography (including digital media); and artifacts.

“Our students develop skills and treatment approaches so they can specialize further or remain generalists and deal with anything,” Dr. Smithen says.

The program was founded in 1974 by Ian Hodkinson, now professor emeritus, who proposed and campaigned for the program and obtained federal funding. It launched with streams in fine arts and artifacts.

Prof. Hill lauds the “ongoing increase in science literacy of students in the program and the ability to undertake complicated technical analysis.” An “outstanding” component of the program is that students in conservation science streams complete a research thesis, while those in treatment streams must identify their specialization and execute a major research project.

A current student, John Habib, has an undergrad in chemistry from Queen’s and is doing a technical analysis of materials used in a Coptic Egyptian manuscript from the 18th century. “He really amplifies the best of what is involved in art conservation,” Prof. Hill says, “in that it truly is an intersection of arts and science.”

Sally Gunhee Kim has done a lot in the years since she left Queen’s.

Ms. Kim (Artifacts Conservation, MAC’19) already had a BA in physical chemistry and visual arts from Brown University, the Ivy League campus in Rhode Island.

Since Queen’s, she was named Emerging Conservator for 2021 by the Canadian Association for the Conservation of Cultural Property (CAC), and spent two years as the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. Recently, she started as objects conservator at the Royal BC Museum, where she pursues her twin passions of preserving Indigenous cultural heritage and promoting accessibility and equity in the field of conservation.

“I collaborate with collection managers and technicians to help design preventive care of various collections, ranging from natural history specimens to modern history artifacts and Indigenous belongings,” Ms. Kim says. Her current tasks include providing recommendations and guidelines on preparing and packing collections for the move to the museum’s new building, now under construction.

Ms. Kim, who is deaf, says that at Queen’s she “felt welcomed, known, valued, and encouraged to bring in my Deaf perspective to the graduate program and beyond.” And she has taken that perspective beyond; she later successfully pushed for standing status for the CAC’s Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility committee, and is currently chair of the committee.

She also helps to select objects from the museum’s collection for loans and exhibits elsewhere in Canada.

“Please be on the lookout for exhibits happening at and travelling beyond the Royal BC Museum!”

Such analysis has been aided by funds from the Jarislowsky Foundation and Bader Philanthropies and includes an M6 Jetstream scanning X-ray fluorescence spectrometer – the only one of its kind in an educational institution in Canada. Funding has also been donated by the Bader family for a Bader Chair in Art Conservation (Dr. Aaron Shugar) and a post-graduate Bader Research Fellow in Conservation. (The first fellow, Megan Creamer, now works at the Art Institute of Chicago, while the second and current fellow, Lindsay Sisson, will soon leave to work for Ingenium in Ottawa.)

There has also been a fundamental shift from a “Eurocentric approach” when dealing with Indigenous objects and groups – a shift that is still happening in conservation in museums and galleries across Canada and in many other countries as well.

“Really huge changes started in the late ’80s and early ’90s,” says Prof. Hill, who graduated from the program in 1989 and returned as a professor in 2013. “I’m proud to say that one of the leaders in those changes was one of our graduates, Miriam Clavir [MAC’76].” (Miriam Clavir is now conservator emerita at the Museum of Anthropology at UBC.)

“She was really one of the first conservators in Canada, and certainly in North America, to have a community-based approach to working with Indigenous belongings.”

In 2026, the art conservation labs will move into the new facility, alongside the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, also funded by the Baders. Norman Vorano, Head of the Department of Art History and Art Conservation, hopes that move will help to facilitate a kind of cross-fertilization between art history, fine art, and art conservation.

“We are very excited by the new building because it gives us the space to create new academic and training possibilities, such as a new PhD program,” Dr. Vorano says. “That would promote more innovative research and teaching using the technologies in art conservation, while promoting more synergies between art historians, artists, and art conservators.”

The existing art conservation program is “a real jewel in the university’s crown,” he says. “It’s a jewel that not a lot of people know of, even members of our own Queen’s community.”

Martin Jürgens is an example of the art conservation program’s expansive international scope.

Mr. Jürgens (Paper Conservation, MAC’01) was born in Brazil to an English mother and a German diplomat father, grew up in Brazil, Japan, Chile and Germany, studied photography and design in Germany, later studied preservation in New York State, and then came to Kingston to study at Queen’s. Now he lives in Amsterdam, where he’s a photo conservator at the Rijksmuseum, and is currently a PhD candidate at De Montfort University in Leicester, England.

“Officially, it’s in the history of photography,” he says of his PhD. “Because I’m a conservator, I’m coming from a scientific, technical point of view, and I’m trying to figure out how that works in the historical setting.”

Mr. Jürgens’s international experience grew when, while a freelance conservator based in Germany, he helped to establish a photographic archive at a Buddhist monastery in Laos.

“I was giving advice on photograph conservation and preservation – and in a tropical climate,” he says. “Dealing with that in a communist and anti-Buddhist setting was really challenging on many levels, including climate and culture and language. But that was such a great project.”

He recalls that at Queen’s the “quality of teaching and learning was very high” and he cites Adjunct Professor Thea Burns as having been “very good and very precise, with a very high level of knowledge. She taught us how to think things through and not jump to conclusions.”

The university was welcoming and “felt very much like home,” he recalls, though not everything was so warm.

“I’ve never really experienced winters like that,” he says. “So, that was kind of new for me.”

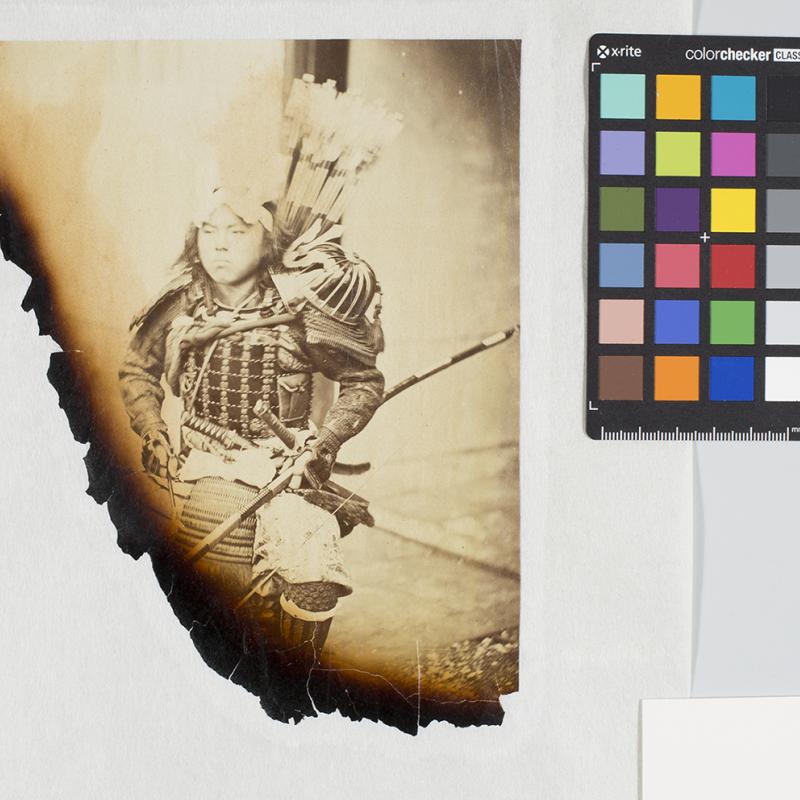

The above images, attributed to Felice Beato and created around 1865-1870, show before and after conservation of a Japanese albumen print that had been damaged in a fire. The image was extremely brittle and unable to be safely handled. Martin Jürgens and others flattened the curled print, consolidated the charred areas, then lined the image with a thin sheet of Japanese paper to give it physical stability. Finally, the print was mounted in a folder for storage and exhibition.

Ashley Amanda Freeman is from Chicago, got her second master’s in Canada, and got her PhD in Norway. Fortunately, she says, “I’m quite fond of winter.”

So, what’s she doing in sunny Los Angeles? The short answer is – well, with Dr. Freeman (Conservation Science, MAC’13) there are no short answers. Her enthusiasm for conservation is such that she’s happy to talk all day about every aspect of it, from hygroscopic materials to “the effect of nano-sized particles in gesso” and, in general, “focusing on how the mechanics of an object change when the environment is changing.”

This quality makes her ideally suited to talk to students or others about the intersection of science and conservation, and she is committed to doing so. A long list of former professors, fellow students, and colleagues have helped her clarify her own aspirations in her fields of chemistry and conservation science, she says, and now she often works with interns in similar ways.

“I learned how important it is to foster that type of growth for somebody.”

Before Queen’s, Dr. Freeman earned a master’s degree in chemistry from Loyola University Chicago, and afterward she completed her PhD in mechanical and industrial engineering at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Currently, she’s on staff at the Getty Conservation Institute, perched on an arid hill near the J. Paul Getty Museum overlooking L.A. She works on preserving cultural heritage by examining the impact of environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, on cultural heritage objects. Previously, she worked at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and still volunteers there on research projects.

Jocelyn Hillier is a recently minted example of how Queen’s competes with graduate-level art conservation programs in the United States.

Ms. Hillier (Paintings Conservation, MAC’23) has both Canadian and American citizenship, and continues to have a bifurcated relationship with the two countries.

“I was born and raised in Canada, but hold American citizenship,” Ms. Hillier says. “I have only worked in American institutions and American studios, while I have received all of my education in Canada.”

Her border straddling has now gone international, as she is working at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, on a Fulbright fellowship in collaboration with the organization American Friends of the Mauritshuis.

The Dutch connection was elemental to her decision to study at Queen’s.

“The Queen’s Art Conservation program has great connections to the Agnes [Etherington] gallery on campus, which has a very impressive art collection, specifically in the Dutch Golden Age, which is my main area of interest.”

At Queen’s, she was invited to participate in a collaborative research study in which the Mauritshuis and the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University would conduct a series of technical analyses on Rembrandt tronies, which are character studies that were frequently produced by the 17th-century Dutch master and his workshop.

Queen’s had recently acquired its X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, “and one of the first things that we scanned with it was the Rembrandt … It was a genuine honour to be able to work on that project.”

Don’t ask Ms. Hillier what secrets they discovered buried within the work of the Dutch master.

“We haven’t published all of our information, so I’m not necessarily able to say some of the profound results that we found,” she says, and smiles. “It’s very, very exciting for me.”