|

|

|

|

Lake George. Site of public beach on Lake George (Kings County, Nova Scotia, Canada). Recent increases in algal production have been linked to decreased grazing by Daphnia as a result of calcium decline. Image courtesy of Joshua Thienpont (Queen's University). |

Algal bloom. An algal bloom in a lake near Parry Sound, Ontario, located on the Canadian Shield, another region of Canada experiencing lakewater calcium decline. Image courtesy of Andrew Paterson (Ontario Ministry of the Environment). |

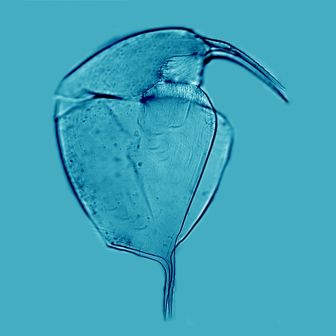

Fossil Daphnia pulex (water flea) claw. The postabdominal claws of the openwater cladoceran Daphnia are well preserved in lake sediments. Decreased abundance of Daphnia claws in the sediments of Lake George correspond to increased inferred algal production. Daphina pulex have high calcium requirements, and are at a competitive disadvantage when calcium concentrations decrease in lakes. Note, highly magnified microscope image. Image courtesy of Jennifer Korosi (Queen's University). |

|

||

|

Typical Nova Scotia recreational lake. Located near Halifax, NS. Image courtesy of Joshua Thienpont (Queen's University). |

Lake George, NS. Cottages surround much of Lake George. Increased algal production is one of the greatest concerns for lake managers. Image courtesy of Joshua Thienpont (Queen's University). |

Bosmina sedimentary remains. Most body parts of the open water cladoceran species Bosmina are well preserved in lake sediments. Bosmina are tolerant of lower calcium waters. Due to their smaller body size they are less effective grazers on algae than Daphnia. Image courtesy of Jennifer Korosi (Queen's University). |

|

|

||

|

Little Wiles Lake (Bridgewater, NS). Daphnia populations in Little Wiles Lake crashed around 1970 when calcium levels fell below 1.5 mg/L. Image courtesy of Jennifer Korosi (Queen's University). |

Sectioning a sediment core. After retrieving a sediment core from the lake bottom, the core is sliced into discreet sections which represent a specific amount of time. For complete details on the paleolimnological methods used in this study, view our methods pages. Image courtesy of Joshua Thienpont (Queen's University). | Collecting a sediment core. The removal of a 7.6 cm (3") diameter sediment core from a lake in Nova Scotia is carried out from a canoe. For complete details on the paleolimnological methods used in this study, view our methods pages. Image courtesy of Joshua Thienpont (Queen's University). |

| Sectioning a sediment core. High-resolution sectioning of a sediment core into 0.5 cm slices (each representing between 2-10 years) allows detailed analyses of changes in the lake's history over time resulting from environmental changes. Image courtesy of Joshua Thienpont (Queen's University). | Daphnia mendoatae. An example of a calcium-rich species, Daphnia are important grazers on algae in lakes. Image courtesy of Shelley Arnott (Queen's University). |

Alona sedimentary remains. Most body parts of the shallow water cladoceran species Alona

are well preserved in lake sediments. Image

courtesy of Jennifer Korosi (Queen's University). |

|