What the invasion of Ukraine means for the IPCC’s latest climate change report

April 19, 2022

Share

The UN’s new IPCC report on the mitigation of climate change says that immediate and deep emissions reductions are needed to limit global warming, along with removing carbon dioxide back out of the air in future. Meanwhile, the world’s governments are urging fossil fuel companies to drill for more oil and gas as fast as possible to make up for sanctions on Russia. What on earth is going on?

The job of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) is not to conduct research or to express opinions, but to assess the scientific literature. This primarily means papers accepted in academic journals prior to a cut-off date. In the case of this latest report, that was back in October 2021.

The job of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) is not to conduct research or to express opinions, but to assess the scientific literature. This primarily means papers accepted in academic journals prior to a cut-off date. In the case of this latest report, that was back in October 2021.

Since then, wholesale prices of most fossil fuels have more than doubled. So, what to make of the IPCC’s conclusions? Does Russia’s invasion of Ukraine make it easier or harder to stop climate change? The answer depends heavily on how you frame the problem.

Using the “emitter responsibility” framing adopted by the IPCC – and hence by almost everyone else, including the world’s governments and corporations – climate change means emitters need to reduce “their” emissions. Vendors of the products that cause those emissions are mere bystanders.

Under this framing, a period of high fossil fuel prices that may be ushered in by the Russian invasion has mixed implications. On the one hand, higher prices and a new awareness of the geopolitical risks of relying on imported fossil fuels will increase incentives to invest in alternatives like renewable or nuclear power.

On the other, higher costs and inflation are placing pressure on public and private finance available for the transition, and triggering a rush to increase consumer fossil fuel subsidies (supposedly on the way out after the Glasgow climate pact) and invest in non-Russian fossil fuel production and infrastructure.

Most worrying, higher fuel prices threaten to drive a tank through the delicate balance of incentives carefully designed (like some Heath Robinson cartoon) to keep the impact of climate policy on consumers just below the political radar. Populists the world over are honing their soundbites.

There is another framing: “producer responsibility”. Of the fossil carbon we dig up or pump out, 99.9% of it enters the active carbon cycle, continuing to prop up global temperatures for millennia. In the end, to stop climate change we need to safely and permanently “refossilise” all the carbon dioxide we generate from fossil sources, either by reinjecting it back underground or otherwise turning it back into rock.

Right now, we permanently dispose of less than 0.1% of the carbon we dig up. To meet the goals of the Paris agreement, we simply have to increase that fraction to 100%, one thousandfold, over the next 30 years.

Capture carbon – and still make profits

Which brings us back to Ukraine. The invasion has highlighted both the dangers of ignoring producer responsibility for fossil fuels, and an opportunity to embrace it. Who are the producers? The vast bulk of fossil carbon dioxide comes from products produced and sold by fewer than than 80 companies – all of whom are doing rather well at the moment.

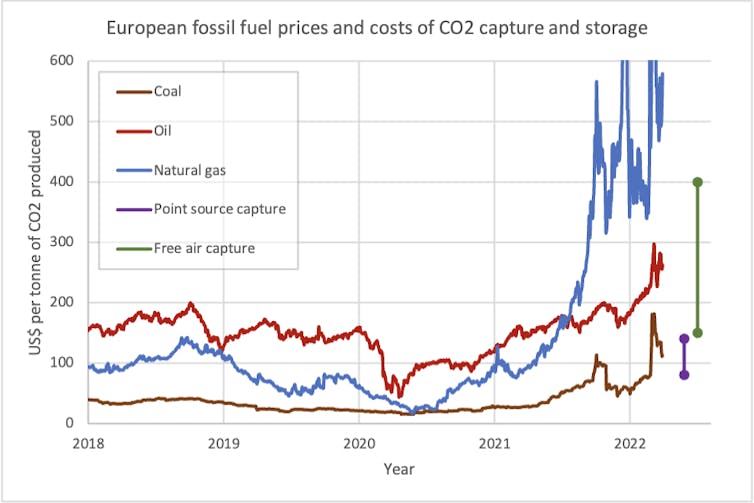

European wholesale prices of oil and coal have increased over the past year by about US$140 (£110) per tonne of carbon dioxide they generate, natural gas by more than US$350 (£270). That is more than the cost of capturing all that carbon dioxide and reinjecting it back underground.

Companies have been capturing carbon dioxide for decades at source for incentives of around US$60 (£50) per tonne and are already gearing up to build plants to capture it out of thin air for incentives of around US$300 (£230) per tonne. So it can be done. The question is whether these plants can do it on a large-enough scale to make a difference, and there is only one way to find out: make them.

Of course, consumers still have a role to play: disposing of all that carbon dioxide will inevitably make fossil fuels more expensive, so it makes sense to cut down. And government regulation, like the “carbon takeback” idea, is essential to make this happen. We certainly can’t expect the industry to do it purely out of the goodness of its heart.

But at today’s prices, fossil fuel producers could prevent the products they sell from causing global warming and still make the same profits they were making a year ago. Instead, this giant cash machine is reinforcing investors’ and governments’ addiction to fossil fuel rents and funding exploration for new resources that, if we don’t work out how to stop fossil fuels from causing global warming, we won’t be able to use.

The IPCC cannot adopt this “producer responsibility” framing because it would imply a change of emphasis in climate mitigation policy. Fossil fuel exporting countries would certainly veto any such clarity because, they would argue, they are working hard to reduce their own emissions, and what happens to the fuels they export is someone else’s problem.

This is like a chemicals company volunteering to take care of ozone layer-destroying CFC emissions from its own factories, while arguing that CFCs aren’t doing any harm as long as they are locked up in an aerosol can, so it couldn’t possibly be held responsible for ozone depletion caused by the products it sells.

The IPCC, 30 years ago, was deeply involved in establishing the framing of “emitter responsibility”. That was only half the story then, and it is only half the story now. Until we adopt the principle that anyone producing or selling fossil fuels is responsible for disposal of all the carbon dioxide generated by their activities and products, we aren’t going to stop climate change. And when we do, we will. It really is that simple.![]()

________________________________________________________

Myles Allen, Professor of Geosystem Science, Director of Oxford Net Zero, University of Oxford and Hugh Helferty, Adjunct Faculty, Department of Chemistry, Queen's University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.