The obesity paradox: Obese patients fare better than others after heart surgery

October 2, 2020

Share

The World Health Organization has declared obesity to be a global epidemic that “threatens to overwhelm both developed and developing countries.” However, is obesity always bad when it comes to health?

Certainly, obesity is a significant risk factor for the development of many chronic conditions, including heart disease. However, research has shown that in a number of situations, being overweight may actually be of benefit. This phenomenon has been called the “obesity paradox.”

Certainly, obesity is a significant risk factor for the development of many chronic conditions, including heart disease. However, research has shown that in a number of situations, being overweight may actually be of benefit. This phenomenon has been called the “obesity paradox.”

Our group from the departments of public health sciences and anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at Queen’s University investigated the relationship between body mass index (BMI, a commonly used ratio of weight to height) and outcomes after heart surgery. We analyzed a large database of health records of almost 80,000 patients having open coronary bypass surgery in Ontario over a 13-year period using data from ICES, a not-for-profit research institute in Ontario. We tracked five-year survival rates as well as complications occurring during the year after surgery.

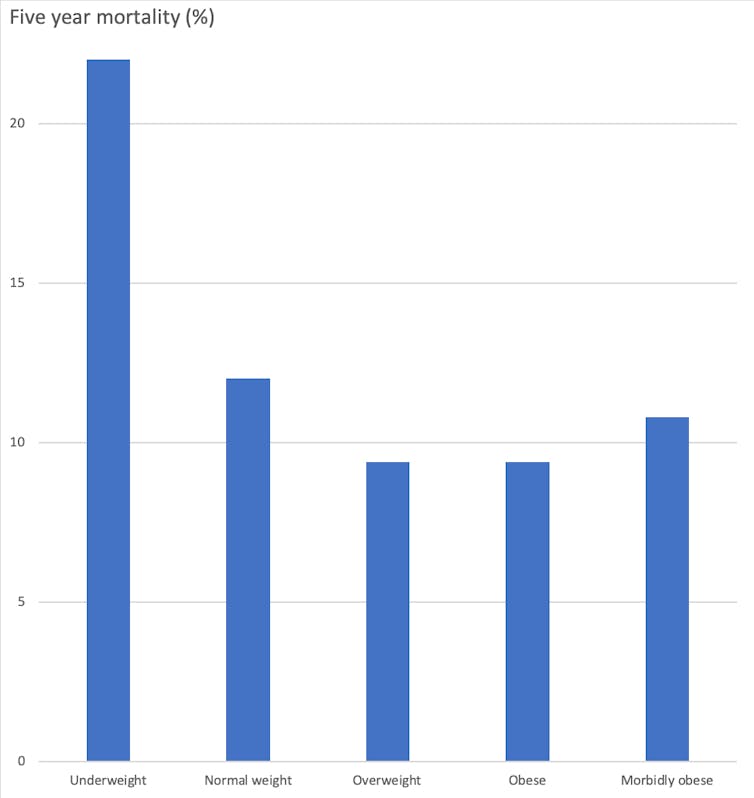

We found that patients in the overweight and moderately obese categories made up two-thirds of all cardiac surgery patients. However, these patients actually had lower death rates and complications than patients in the normal weight, underweight and morbidly obese categories.

The highest risk of complications was seen at the extremes of BMI, meaning patients in the underweight and the morbidly obese categories. Such a relationship has also been found in other patient groups with different medical conditions or procedures.

Economies of scale

In addition to the difference in complication rates, there are economic implications for these findings. We analyzed the financial costs of coronary bypass surgery and the medical care during the year following surgery in a group of over 53,000 patients over a 10-year period.

Not surprisingly, due to the disproportionate number of patients in these categories having heart surgery, overweight and obese patients accounted for the overall majority of health-care costs, a total of $1.4 billion (in 2014 Canadian dollars), compared to $788 million for the other BMI categories combined. However, the average cost of care per patient in the overweight and obese categories was substantially lower than in the normal weight, underweight and morbidly obese categories.

Weighing in on weight gain

This does not necessarily mean that weight gain should be recommended to reduce these risks. The scientific literature is consistent that obesity and lack of fitness are associated with cardiovascular disease, as well as many other risk factors for heart disease such as high blood pressure and diabetes.

However, once the need for surgery is determined, having excess body fat may provide increased energy reserves during a period of stress and healing that are not available to lower-weight patients. This advantage is lost in the case of extreme obesity, where the common presence of other related diseases and reduced mobility after surgery likely contribute to the increased complication rate.

The perils of frailty

On the other hand, we found that being underweight is associated with increased mortality in hospital patients and increased health costs. In fact, low BMI is more detrimental to the recovery from heart surgery than even extreme obesity. This may reflect the negative effects of frailty, which has been shown to adversely affect recovery from surgery.

In addition to reduced body fat, patients in the underweight category typically have reduced muscle mass, which limits function and mobility even before surgery. That leaves them with little in reserve to resist the stress of major surgery and the prolonged recovery period afterwards.

Even when taking advanced age and other diseases into account, low BMI was independently associated with death and other complications after heart surgery. This suggests that patients who are frail might do better after surgery if — time permitting — they were offered an exercise and nutrition program before surgery.

What is normal anyway?

It’s also important to look at the BMI category that was considered to be the standard for comparison: patients in the so-called “normal” weight category. This is generally considered the optimal BMI and the target for most fitness strategies. However, in our study and others, patients in the normal weight category had worse outcomes than patients in the overweight and moderately obese categories.

Importantly, these results do not mean that fattening up the population in the normal weight band should become a public health goal.

First, as mentioned, patients who are overweight have a far higher risk of developing heart disease in the first place, and an ounce (or gram) of prevention is a much more effective health strategy than a pound (or kilogram) of cure. Improving the fitness of the population is one of the most important public health strategies for reducing heart disease and the need for heart surgery in the first place.

Second, it may well be that what is an optimal BMI in other situations should not be considered optimal for recovery from surgery, and so it would make sense to define a “normal” BMI according to the specific situation. In this sense, the obesity paradox might not be a paradox at all.

This article was also co-authored by Dr. Brian Milne, professor emeritus, anesthesiology and perioperative medicine, Queen’s University.![]()

____________________________________________________________

Ana Johnson, Professor, Department of Public Health Sciences, Queen's University and Joel Parlow, Professor, Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Queen's University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.