Indigenous child welfare is grounded in community and children’s needs

February 5, 2021

Share

The recent enactment of Bill C-92, an act “respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families,” will shift Indigenous child welfare to Indigenous-operated organizations, and is expected to come with many positives for the families and communities it focuses on: First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

The impacts of Bill C-92 are not expected to be a panacea, given it comes after the many decades of the tragedies of the Sixties Scoop and residential schools. These have been well documented by Gitksan researcher and activist Cindy Blackstock, the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, the Assembly of First Nations, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and many others.

The impacts of Bill C-92 are not expected to be a panacea, given it comes after the many decades of the tragedies of the Sixties Scoop and residential schools. These have been well documented by Gitksan researcher and activist Cindy Blackstock, the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, the Assembly of First Nations, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and many others.

While the bill is not expected to immediately turn things around, there were already positive changes afoot across Canada that should be highlighted and celebrated.

Indeed, as stressed by Kenn Richard, a founder of Native Child and Family Services of Toronto, “Indigenous approaches emphasize the importance of family and collectivity as a place for safety, and healing. The learning opportunities from this project and others happening now in Indigenous child welfare services can be instrumental in informing improved practices throughout the wider sector.”

Where children belong

One recently concluded pilot program in Manitoba, focused on strengthening belonging for children, is notable for its many successes.

A few years ago, the Toronto-based charity Until the Last Child launched and funded an innovative “co-created model” called Bringing Families Together (BFT). This two-year multi-stakeholder project was undertaken in partnership with the Government of Manitoba, the four child welfare authorities representing about 11,000 kids in government care, representatives from Indigenous communities, the University of Manitoba and Deloitte Canada.

We both worked in different capacities on the project. Verla, who is First Nation from the Pimicikamak Cree Nation (Cross Lake, Man.) and speaks her Cree language fluently, was a BFT family finder team member over the course of the two-year pilot. Philip was a member of the evaluation advisory committee for the project.

Not surprisingly, much research has shown that without a strong sense of family, community connection and belonging, children in care often experience poor outcomes that may impact their whole lives.

The Bringing Families Together project had a lofty goal: to achieve a success rate of at least 75 per cent of permanent belonging solutions for 150 children and their families over the two-year period. It achieved 76 per cent over the pilot period. That is laudable given that the BFT team of committed and trained staff received referrals only for children and youth (and their families) for whom child welfare authorities had encountered the most difficulty in building a strong sense of belonging and lifetime family support commitments. For example, at referral to the pilot staff, none of the children were living in family-related placements.

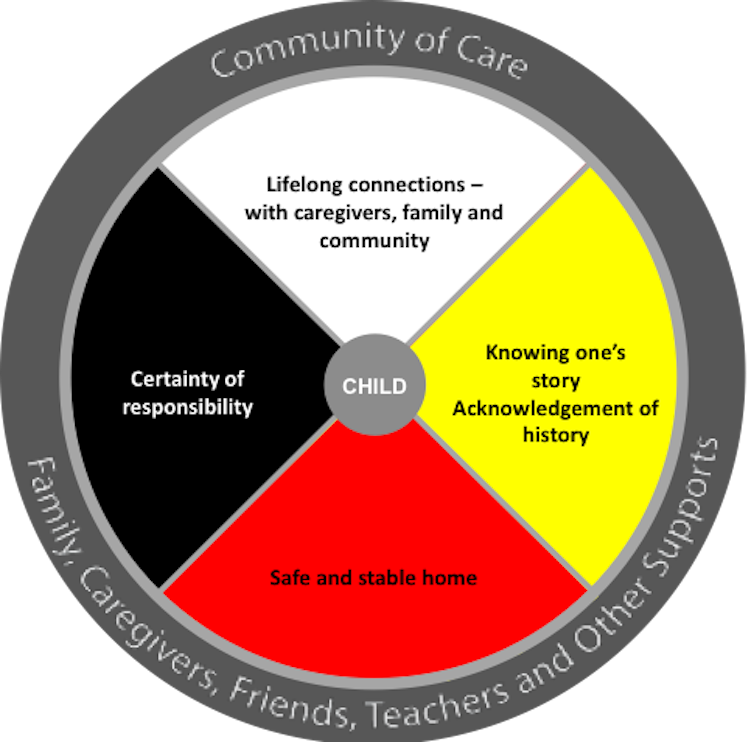

The team developed a four-part definition of belonging and permanency. It encapsulated several important components that placed the child at the centre of the project work.

Each of the components in the medicine wheel quadrants represent a crucial and interconnected requirement of belonging and depicted in a culturally accessible and positive fashion. Each part was deemed by the partners to best ensure any child is supported and experiences a sense of belonging. While the project has concluded and the staff team have moved on to other roles, a couple of other similar pilot projects have followed.

Success stories

A detailed evaluation of the program confirmed that the high belonging and well-being target of 75 per cent was achieved and slightly surpassed for children and youth served by the BFT staff team. And significantly, 62 per cent of these children were now being cared for by family members.

The importance of this project was not lost on the many engaged parents and community members. In the words of one of the participating foster parents: “You must know where you come from — it gives you a sense of belonging and culture.”

The general findings of the project have served to underpin and launch several additional pilots in Canada and other countries. There is confidence from the evaluation conducted that the trajectory of children’s lives was positively affected. Those children and youth helped by the project staff, versus a comparison group receiving regular child welfare services, experienced fewer breakdowns in placement and higher rates of long-term commitment from family members and foster parents. In many instances children left care altogether.

And so, as Bill C-92 rolls out and begins to change the face of child welfare in many parts of Canada, let’s not ignore opportunities to learn about recent innovations and successes that can positively change lives for children and youth as well.![]()

______________________________________________________

Philip Burge, Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Queen's University, Ontario and Verla Umpherville, Child and Family Services Worker, Pimicikamak Cree Nation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation is seeking new academic contributors. Researchers wishing to write articles should contact Melinda Knox, Associate Director, Research Profile and Initiatives, at knoxm@queensu.ca.