Indian day school survivors are seeking truth and justice

October 27, 2020

Share

In January 2020, Canada began accepting claims emerging from a billion-dollar settlement with survivors of the Indian day schools. This landmark settlement has been embroiled by legal battles as well as additional lawsuits. In the meantime, survivors and the public have yet to learn how the $200 million, earmarked for education, healing and commemoration, will be used.

An estimated 200,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend Indian day schools that operated on First Nations reserves in every Canadian province from the mid-1800s until 2000. While the government of Canada funded the schools, the daily operations were run by the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian and Methodist churches and, later, the United Church of Canada.

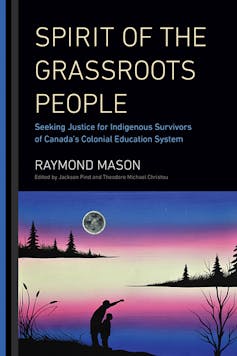

We have collaborated on a new historical biography, Spirit of the Grassroots People: Seeking Justice for Indigenous Survivors of Canada’s Colonial Education System. The perspectives we bring are as an Indian day school survivor and activist (Raymond), author of this book, a mixed settler-Anishinaabe historian (Jackson) and a white settler scholar of education (Theodore), the book’s editors.

As historians of education, we believe that Canada must continue to come to grips with the full extent of its past. Schools and curricula are a part of this past, as well as the present and the future. They also laid the historical foundation of inequality for Indigenous students.

Forced attendance, abuse

Since the official submission date for claims opened in January 2020, survivors have been navigating the confusing and lengthy written application of documenting their trauma and abuse.

While the settlement covers the costs for survivors to file a claim with the designated legal counsel, only recently have survivors been able to hire their own lawyers, who they themselves must pay. In June of this year, survivors also learned that they cannot change the level of claim they previously submitted.

Survivors who submit an application are entitled to a minimum of $10,000 for “harms associated with attendance” at one of the 699 recognized schools.

This does not include the approximately 700 Indian day schools that the federal government excluded from the settlement. Former students who were physically or sexually abused could receive between $50,000 to $200,000 based on “severity of the abuses suffered.”

This federal settlement was reached after extensive advocacy work by survivors.

Survivor Garry McLean, with Raymond, approached lawyers in 2016 after spending the previous seven years building a network of survivors and submitting a claim within the Manitoba court system. After extensive negotiations with the federal government, there was an announcement of an agreement in principle on Parliament Hill in December 2018. After additional negotiations, the final settlement worth $1.47 billion was announced in August 2019.

Survivors’ work has opened up processes of legal acknowledgement of wrongdoing and thus made possible a form of justice and compensation. As of Sept. 30, 2020, the settlement had received 84,427 claims and paid 27,690 survivors with another 56,737 applications still under review.

National inquiry into day schools

It has been over five years since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) presented their findings in a report and in Calls to Action. Since that time, ongoing injustices towards Indigenous people have led some to debate whether reconciliation is already dead. Yet the truth that was uncovered through oral testimony and historical research as part of the TRC has provided valuable knowledge to those who are listening.

Numerous departments in universities, colleges and public schools have begun incorporating the history of Indian residential schools into their curricula.

This process of seeking the truth is unfortunately not happening for Indian day schools survivors, despite an estimated 2,000 individuals who are passing away every year. It is time for a national inquiry into the history of Indian day schools and their ongoing legacy for the education of Indigenous students in Canada.

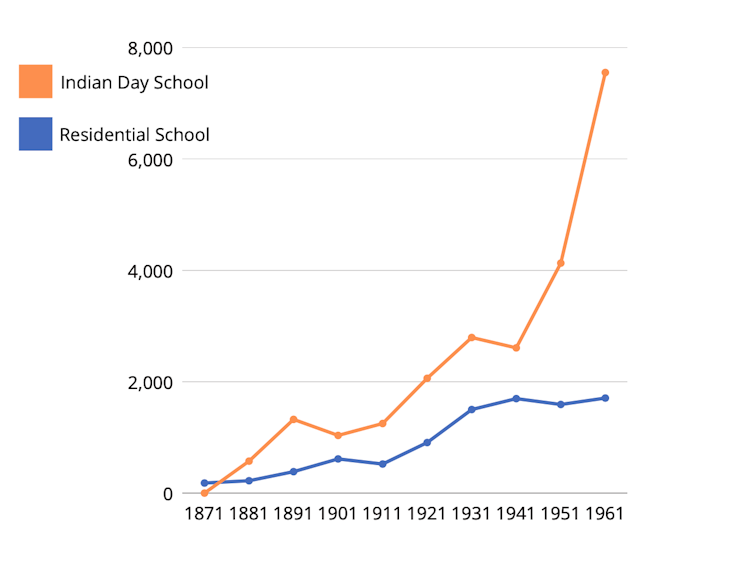

Helen Raptis, who has studied the history of Indian day schools in British Columbia, has argued that our understanding of Indigenous education “has been hampered by historians’ almost singular focus on residential schooling.” This is despite the fact that more students attended an Indian day school than a residential school in Canada.

Abuse, forced to abandon language

When the federal government, plaintiffs and lawyers announced the day schools agreement in principle in December 2018, Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations Carolyn Bennett, acknowledged:

“As a result of the harmful and discriminatory government policies at the time, students who attended these schools were subject to sexual, physical and psychological abuse and forced to abandon their language and culture. Survivors across this country continue to suffer from the abuse and horrific experiences they were subjected to, which were perpetuated by the very people charged with educating them as children.”

Since this announcement, neither the government nor any of the religious organizations involved, have launched a national inquiry or issued a formal apology. If the federal government and church organizations are unwilling to support an investigation into the full extent of survivors’ accounts of abuse, then historians and the general public must make it a priority to learn this history.

Indian day school survivors and their descendants have already begun sharing their schooling experiences. Through organizing and sharing information about their claims and experiences on a growing Facebook group and articles by journalists such as Ka’nhehsí:io Deer, their stories are slowly becoming heard. The nearly 20,000-strong Facebook group offers mentors, guidance and a supportive community for survivors. This virtual place has become a primary source of information for claimants.

Mapping Indian day schools

From the perspective of survivors, such private forums are critical. However, they cannot replace the need for publicly accessible records, including digital records, for future generations of survivors’ descendants, historians and the general public.

In research at Queen’s University, we are now working towards a map-making project that will provide an online resource that visualizes the location of all Indian day schools and describes what archival files are available.

In addition to this, we invite Indian day school survivors to participate in a study that seeks to learn about their experiences through questions such as: What did you experience in Ontario’s Indian day school? How did these experiences impact you later in life? What would you like to be remembered about the Indian day schools?

These questions are only small steps towards a wider goal of providing an option for Indian day school survivors to tell their history without the interference of the government, lawyers or a claims administrator. The oral history from survivors will play an essential role in the memory of these events as evidenced from the testimonies of survivors of residential schools.

Urgent response required

There is an urgent need to document history related to the day schools, and also to commit to holding Canada accountable for systemic injustices that continue to harm Indigenous lives and communities today.

Sen. Murray Sinclair, who chaired the TRC, has criticized the way the federal government has handled records related to residential schools’ survivors’ accounts. In June, he noted:

This is despite the TRC’s call for a national review of archival policies. An ongoing battle over the records of residential school survivors stories and missing files is still an issue more than a decade later.

We believe that all Canadians must join with survivors in demanding transparent processes in the Indian day school settlement. This would involve funds being available to the legacy fund for the support of healing and education.

Seeking truth in history should begin with study of our educational systems. These embed our values and beliefs. The Indian day schools are a part of Canada’s history and directly affect every Canadian, not only those who survived them.![]()

____________________________________________________________________________

Jackson Pind, PhD Candidate, Indigenous education, Queen's University; Raymond Mason, Community research partner, Peguis First Nation, and Theodore Christou, Professor, Social Studies and History Education, Queen's University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.