Understanding bleeding disorders

April 16, 2019

Share

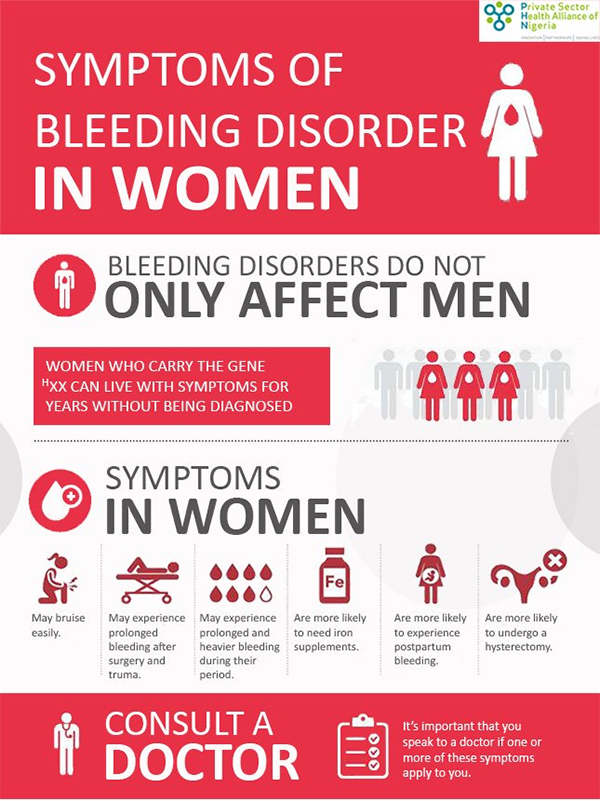

About 30 per cent of all women report heavy menstrual periods at some point during their reproductive years. Up to 15 per cent of these have an underlying bleeding disorder and yet most have never been diagnosed, leaving thousands of women to suffer from a treatable problem.

As a hematologist and clinician scientist at Queen’s University who cares for patients with inherited bleeding disorders, it is a major source of frustration for me that women with bleeding disorders can wait up to 15 years to get appropriate testing and treatment.

As a hematologist and clinician scientist at Queen’s University who cares for patients with inherited bleeding disorders, it is a major source of frustration for me that women with bleeding disorders can wait up to 15 years to get appropriate testing and treatment.

I worry even more about what happens to those who never get diagnosed. These women are at risk of acute hemorrhages leading to blood transfusions and the need for hysterectomy.

Because April 17 is the 29th annual World Hemophilia Day — a day focused on outreach and education about hemophilia — I would like to share some evidence-based information about heavy periods, what it means to be a female “carrier” of hemophilia and how you can easily test yourself for a bleeding disorder.

Iron deficiency and abnormal periods

Bleeding disorders that affect women include von Willebrand disease and hemophilia — both are inherited and are caused by low levels of “clotting factors” (proteins needed for normal blood clotting).

In families with a bleeding disorder, it is common for women to not realize their periods are heavy because other affected women in the family have similar problems. To them, heavy periods seem normal.

Key features of heavy and abnormal periods include having to change pads or tampons more than every hour, having iron deficiency anemia, frequently soaking through your sheets at night and bleeding that lasts longer than seven days.

Key features of heavy and abnormal periods include having to change pads or tampons more than every hour, having iron deficiency anemia, frequently soaking through your sheets at night and bleeding that lasts longer than seven days.

Iron deficiency anemia is of particular concern because it leads to fatigue and shortness of breath as well as poor school and job performance.

Iron deficiency and heavy periods are too often ignored but can be signs of an underlying bleeding disorder. Both are easily treated once the diagnosis is made.

Women can also have hemophilia

Women who are carriers of hemophilia are very often considered to be “only carriers” — capable of passing on a mutant gene to their children. They may be told this by their doctor. Their bleeding then often goes untreated because of this misconception.

My own research has shown, however, that around 30 to 40 per cent of hemophilia carriers experience abnormal bleeding including heavy periods, post-partum hemorrhage and joint bleeds. Some, but not all, have low clotting factor levels.

Effective treatments for heavy periods in women with bleeding disorders are widely available. These include the oral contraceptive pill and medications like tranexamic acid (that prevent clot breakdown) and desmopressin (that increases clotting factor levels).

Gynecologic options such as the levonorgestrel intrauterine device (IUD) and endometrial ablation also exist.

In rare cases, women with bleeding disorders require clotting factor infusions to control heavy periods. If iron deficient, iron supplementation is a key component of treatment as it improves quality of life. Dietary iron intake alone is not enough to correct iron deficiency, particularly once it has caused anemia.

Historically, much of the focus of research and education for hemophilia was on improving treatment for boys and men with the disease. The mainstay is frequent intravenous infusions of the missing clotting factor. Significant advances have been made including the development of better treatments and the possibility of cure.

Are your bleeding symptoms normal?

Many organizations are now focused on increasing public knowledge about bleeding disorders. The recognition that women can also have hemophilia is increasing through the efforts of organizations like the World Federation of Hemophilia.

Unraveling mysteries in the blood

International research leader earns top honour

New website developed at Queen’s University helps women detect the signs and symptoms of a bleeding disorder

The role of novel therapies for women with hemophilia isn’t clear, and additional research is required to understand exactly why these women bleed. One recent study from my lab showed that the blood clotting system of hemophilia carriers doesn’t react to hemostatic stress (such as trauma) as well as it does in healthy controls. A rapid and sustained increase of blood clotting factors is required to halt bleeding following injury and this was significantly impaired in hemophilia carriers.

If you are wondering if you have a bleeding disorder, the Self-BAT (self administered bleeding assessment tool) is freely available and can tell you if your bleeding symptoms are normal or abnormal.

This tool analyzes information about your bleeding symptoms to generate a bleeding score. A high bleeding score is associated with an increased chance of having an underlying bleeding disorder and should be discussed with your doctor.

Significant advances have been made in understanding the problems faced by women with bleeding disorders. More research and education is needed so that all women are diagnosed and treated properly.![]()

____________________________________________________

Paula James is a professor in the Department of Medicine at Queen's University with cross-appointments to the Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine and the Department of Pediatrics.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation is seeking new academic contributors. Researchers wishing to write articles should contact Melinda Knox, Associate Director, Research Profile and Initiatives, at knoxm@queensu.ca.