A dazzling display

April 27, 2016

Share

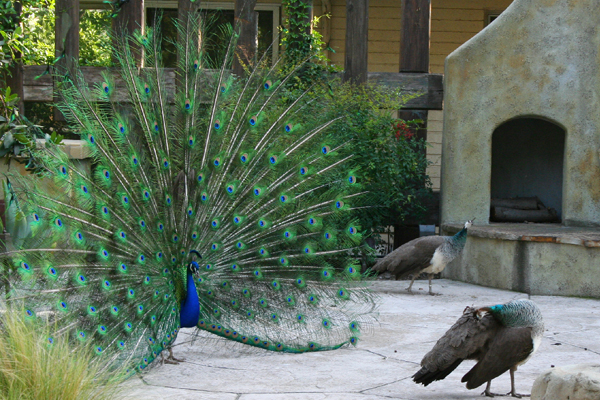

Queen’s University biologist Bob Montgomerie has co-authored a study on the mechanics behind the peacock’s famous mating displays. The research explains the mechanisms behind the male’s courtship dances, including how the structure of the feathers facilitates the peacock’s spectacular display.

(Photo Credit: Roslyn Dakin, UBC)

“Our results suggest that sexual selection – via female choice – may have shaped both the biomechanical design of the eyespot feathers and the behaviours that produce both visual and audio cues,” says Dr. Montgomerie. “Darwin thought that the train-rattling sounds could not be an important courtship signal as the males were already the most beautiful of birds. As the fashion industry always tells us, though, it seems that you can never be too beautiful.”

Courtship displays, such as the peacock’s train display, are used by males in a number of species to demonstrate favorable qualities to potential mates. In the case of the peacock, the male attempts to entice peahens by raising and vibrating his long train feathers. The vibrations both make the feathers rattle and make the brightly colored eyespots appear to hover motionless against a shimmering background.

In this study, the researchers used high-speed video to analyze the "train-rattling" movements of vibrating train and tail feathers in 14 adult peacocks in the town of Arcadia, Calif., where hundreds of peafowl run free. They measured the vibrations of individual tail feathers in the lab and found that displaying peacocks vibrate their tails at or near resonance frequency; giving the long train feathers the greatest vibrational amplitude while minimizing energy expenditure.

Scanning electron microscopy revealed how the tail eyespots stay relatively motionless during displays. Montgomerie and his colleagues found that the feather barbs that form the eyespot are locked together with microhooks – akin to Velcro. This makes each eyespot denser than the surrounding loose barbs, keeping it essentially in place as the loose barbs shimmer in the background. Previous research by Drs. Montgomerie and Roslyn Dakin (now at UBC) found that males with more iridescent eyespots had a higher likelihood of success in attracting a mate.

“Females use the eyespot colour when they assess which male to mate with, and the shaking makes those eyespots stand out in a fabulous display,” says Dr. Montgomerie. “Females undoubtedly use other male traits when making a choice, but previous research has shown that the blue-green colour on the eyespot accounts for about half of the variation in male mating success. Peahens probably mate only once every breeding season but they spend weeks assessing males before deciding who to copulate with.”

The study, titled Biomechanics of the Peacock’s Display: How Feather Structure and Resonance Influence Multimodal Signaling, was published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on April 27, 2016. Roslyn Dakin, a former PhD student under Dr. Montgomerie, led the study along with colleagues Owen McCrossan, James Hare, and Suzanne Amador Kane.

A video, summarizing their findings, can be viewed here.