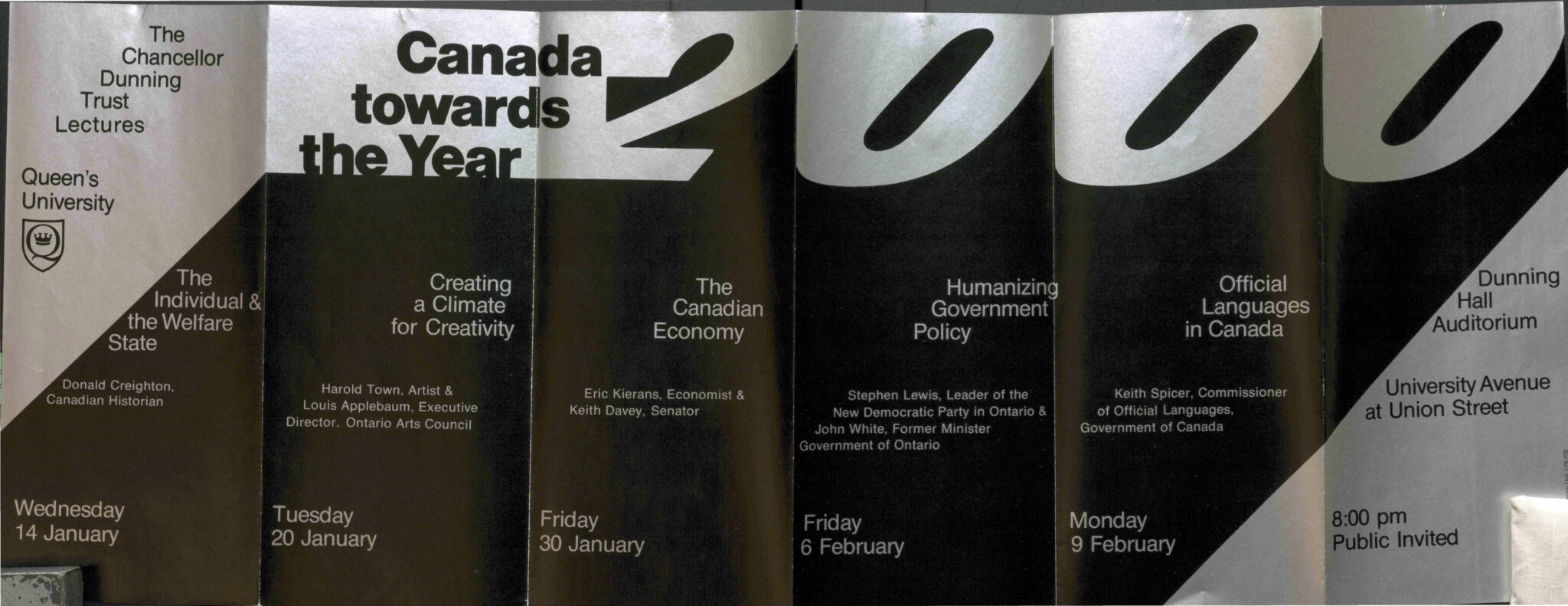

In this Dunning Trust event, Louis Applebaum gave a short address, followed by a reply from Harold Town. The event revolved primarily around the question of how to create an environment to support the arts and artists in Canada, including government subsidies and funding for the arts.

Louis Applebaum was a composer, conductor, and arts administrator. At the time of his Dunning Trust lecture, he was executive director of the Ontario Arts Council, a position he held from 1971-1980. Working on behalf of the Government of Canada as chairman of the Federal Cultural Policy Review Committee, he co-authored the influential Applebaum-Hébert Report, a major review of Canadian cultural institutions and federal cultural policy. Throughout his career, he consulted and composed music with groups including the National Film Board and the Stratford Festival, where he was a composer for over 46 years. From 1960 to 1963 he was a music consultant for the CBC. He also composed music for Hollywood films, earning an Oscar nomination for one early in his career for The Story of G. I. Joe. He was an active arts advisor, serving on the Canadian Council Advisory Council.

Harold Town was a Canadian abstract expressionist painter and a central figure in Painters Eleven, a Toronto group that helped to introduce abstract art to Canada from 1954-60. He was also an illustrator, with work appeared in magazines including Maclean’s and Mayfair. Town was unwavering in his conviction that internationally important and innovative art could develop in Toronto, and he helped foster a new confidence in the Canadian art scene in the mid-20th century. His work represented Canada at the Venice Biennale in 1956 and 1964, and during the 1960s his prints were acquired by the Guggenheim and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He was made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1968. Town regularly defended abstract art in the Canadian media, wrote book reviews for the Globe and Mail, and wrote a regular column for Toronto Life magazine in 1966-71.

During his lecture, Applebaum insisted on the importance of seeing the creative professions as central, rather than ancillary, to our society. The objective, he said, must be to reassign creative people to their rightful place at the centre of our lives, rather than allowing them to be economic anomalies. Talent emerges where opportunity and the time to take advantage of that opportunity (via grants) is provided. While government had a responsibility to fund the arts, Applebaum warned against allowing it to govern the arts. Cultural policies have trouble acknowledging the centrality of change and evolution to the arts, and arms-length organizations like the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council were crucial to prevent government attempts to plan and organize the arts. Ultimately, our efforts should only stop when the poet and the painter are as supported and valued as the doctor and the engineer.

Town took a different approach in his reply. He insisted that Canadian museums needed to focus first on Canadian art, rather than on the great artists from other cultures. He connected this to the trend of other cultural organizations, including theatres and ballets, importing European composers and set designers instead of developing a local pool of talent. He disagreed with the model of government patronage of the arts that Applebaum championed. Town believed that government support could stifle great artists, suggesting that the moment art becomes useful to government it is destroyed. To some extent, he believed, art and artists must remain outside of society to be successful: “The moment that art becomes essential it is lost.”

This lecture was held on January 20, 1976. Listen to it below.