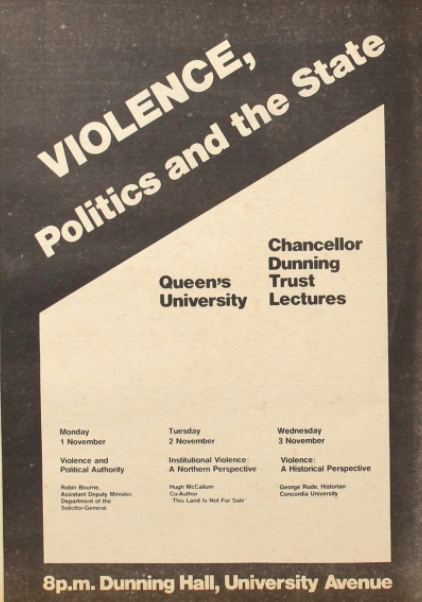

George Rudé was a researcher and writer, author of 15 books, and editor of many others. He was a Marxist historian, greatly influenced by “history from below,” whose research explored the French Revolution and the importance of crowds in history. His best-known work is The Crowd in the French Revolution (1958). His other works include Robespierre: Portrait of a Revolutionary Democrat (1975) and Protest and Punishment: The Story of Social and Political Protestors Transported to Australia, 1788-1868 (1981). After visiting the Soviet Union in 1932, he became a committed communist and anti-fascist. From 1935 to 1959, he was an active member of the British Communist Party. Cold War restrictions on hiring at British universities led Rudé to move to Australia in 1960 to teach at the University of Adelaide and Flinders University. In 1970, he moved to Canada to teach history at Sir George Williams University (later Concordia University), where he remained until his retirement in 1987. In Montreal, he founded the Inter-university Centre for European Studies and was named professor emeritus in 1988.

In his lecture, Rudé introduced his audience to the history of popular or collective violence. He focused on the violence of ‘deprived groups’ through events like peasant revolts, food riots, strikes, and rebellions, rather than governmental or institutional violence. After providing an overview of scholarly debates about why violence occurs, Rude discussed collective violence as a socio-historical phenomenon that changed along with society in France and Britain from 1750-1850. Rude discussed the utility of violence, arguing that violence was a useful tool for deprived groups. He also suggested that the authority of tradition, such as the raising of barricades in France, was an important factor in the success of violent tactics. Finally, he said that a higher degree of organization was correlated with the ability to avoid all but necessary violence because protestors know explicitly what they are fighting for. He concluded by reflecting on the challenges of the late 20th century. New forces, like the rise of the multinational society and deepening political and economic crises, had sharpened the antagonism within countries. In the end, the best answer to “why violence” was not “because they were suffering injustice” but because “there were no other options.”

Listen to his lecture below.