When Prince Charles came to Queen’s University in the King’s town, the day dawned cool and crisp, as you’d expect on the north shore of Lake Ontario three days before Halloween. By 8 a.m., the temperature stood at four degrees. Sweater weather. And before the day was over, the future King Charles III would have a new Fair Isle jumper knitted in Queen’s tricolour to ward off the chill on the forecastle of the Royal Yacht Britannia anchored in Kingston Harbour. But more on that later.

There was mist off the lake the morning of Oct. 28, 1991, though not enough to shroud the midnight-blue hull and three proud masts of the Britannia from students glancing out the windows at Waldron Tower.

The ship had arrived from Toronto sometime during the night, bearing not only the monarch-in-waiting and his fairytale princess, but their sons, William, nine, and Harry, seven. The boys would stay on board as their parents attended a whirlwind of events during a day-long visit to Kingston. Though not all the day’s activities would be at Queen’s, it was the sesquicentennial of the university, chartered by Charles’ great-great-great-grandmother Victoria in 1841, that had earned Kingston a spot on the royal itinerary.

And as with other stops on the royal tour, Kingston seemed to be less excited about the presence of the heir to the throne than about the possibility of catching a glimpse of his charming wife, Diana, Princess of Wales. When the couple had visited Sudbury a few days earlier, Diana’s visit to a cancer treatment centre and her warm and unaffected interaction with patients had been the story. The media duly reported Charles’ tour of a nickel mine, but, as CBC’s Kevin Newman said at the time, “it was Diana’s tour that won the hearts of the people.”

That would change a bit in Kingston. The prince’s tour of Queen’s that day would win him admiration from students, faculty, and the media for the passion of his commitments and his courtly manner.

A crowd of curious onlookers – students, faculty, and townsfolk – began to gather early outside Grant Hall, where the prince and princess were expected by mid-morning to attend a special convocation. Charles was to receive an honorary law degree and give the keynote address. A phalanx of yellow-jacketed Queen’s student constables was already in position on University Avenue, among them 20-year-old Karen Logan, Artsci’94.

She and as many as 100 other student constables had been briefed by RCMP officers that morning. They were accustomed to performing crowd control duties at football games and Alfie’s Pub, but this was different. They were told to defer to official security agents if any issues arose. “We were there mostly for our bodies and highly visible yellow jackets,” remembers Ms. Logan, now a Queen’s governance officer.

Outside the perimeter defined by the student constables, but near the front of the spectators, was Sherri Ferris, then four years into her job as a custodian at Queen’s and five months pregnant. She and the rest of the custodial staff had been busy for more than a week putting an extra shine on the campus sites the prince would visit. For days, she had been busy polishing every glass surface at the John Deutsch University Centre (JDUC), including every pane of the building’s massive oak doors. “I just made it sparkle,” recalls Ms. Ferris, who is still on the job 31 years later.

After all the preparation, she dearly wanted to see the prince and princess make their entrance to Grant Hall and arrived early with work colleagues. Her mother’s family had come from Britain, and Ms. Ferris was fascinated by the monarchy. “For me, it was huge that they were coming to the university and I worked there, I was part of it,” she says.

Sometime after 11 a.m., the royal motorcade came down University Avenue. “I can remember how excited I was that day to see Princess Di,” says Ms. Ferris. “The bumblebee dress. I remember all the details.”

Meanwhile, Farah Mohamed, Artsci’93, was already inside the neo-Romanesque grandeur of Grant Hall. She was one of 900 or so to receive a coveted invitation to the convocation and, for the life of her, she can’t remember why. Was she someone’s plus-one? Did she win some kind of lottery? Regardless, the invite would provide Ms. Mohamed with her first look at the man who would become her boss 31 years later.

The prince spoke of many things in his convocation speech that day – Canadian unity, the soul-affirming powers of good architecture, and, of course, Queen’s 150th birthday. But it was the prince’s comments on the importance of educating and providing opportunities for the young, and of finding an environmentally sensitive and sustainable model of economic development, that resonated with Ms. Mohamed.

After Queen’s, she would pursue a career in politics, then found an international organization to empower young women and, in 2017, become the CEO of the Malala Fund, founded by Nobel Prize winner Malala Yousafzai to champion every girl’s right to education. She would later serve as COO of Canada’s Forest Trust, a company promoting a nature-based path to net-zero carbon emissions.

She was one of 900 or so to receive a coveted invitation to the convocation... the invite would provide Ms. Mohamed with her first look at the man who would become her boss 31 years later.

More recently – in fact, just days before the man she heard speak at Queen’s that October ascended the throne – Ms. Mohamed was named CEO of Prince’s Trust Canada, whose founder and president is His Majesty The King. One of six such organizations internationally, Prince’s Trust Canada focuses on creating uplifting opportunities for young people, assisting veterans to start their own businesses, and providing a sustainable future for Canada.

The prince’s passion at the convocation touched her, she says, and it’s no surprise that the path she took after graduation led her to Prince’s Trust Canada. “It’s not a coincidence,” she says. “Rather, it’s a very nice fit.”

After the ceremony, the prince waded back into the crowd while his wife departed to attend events in town. “He stopped and spoke to someone in the crowd right behind me,” student constable Karen Logan recalls. “I didn’t have a personal interaction with him, but I was there.”

Jenny Corlett, Artsci’94, Ed’95, was in class during all the royal hubbub. She had switched from arts to science that year and couldn’t afford to skip lectures. But she knew her Aunt Mabel was uniquely involved in the festivities and about to make Queen’s history. Again.

Mabel Corlett, Arts’60, was the first woman to receive a degree in geology from Queen’s, and the Geology department’s first female professor in 1969. Now she had created what would become a kind of icon of the royal visit – and it had nothing to do with rocks or minerals.

After stepping away from academic life at Queen’s five years earlier, Dr. Corlett had launched a knitting supply business; the Wool Room sold patterns and the means to make them. For the university’s sesquicentennial, she had designed a Fair Isle sweater in Queen’s tricolour. “She got permission to use the different motifs from the Queen’s coat of arms,” says her niece: “the Q, the thistle, clover, books.”

Mabel Corlett had been selling the anniversary sweater as kits from the Wool Room and donating the proceeds to the Queen’s Bands for new uniforms. For the royal visit, says her niece, she was commissioned by the Queen’s Sesquicentennial Committee to knit a special version of the sweater to be presented to the Prince of Wales. The regal version had a white background and a crown knitted into the back of the collar.

The sweater was waiting for the prince at his next stop, the John Deutsch University Centre, and he accepted it with good humour after unveiling a copy of the royal charter his thrice great-grandmother had granted Queen’s 150 years before.

A luncheon followed at the JDUC, invitation by lottery. Philosophy professor Christine Overall and second-year student Sara (Ubancic) Harrison, Artsci’92, MA’93, Ed’95, were among 300 or so invitees who had been cooling their heels in baronial Wallace Hall since well before the unveiling ceremony, drinking wine and hoping one of the room’s few chairs might become vacant.

Ms. Harrison remembers the free wine was welcomed by the students in attendance and there was a glow in the room by the time the prince finally arrived. Despite the delay, she says, everybody had a chance to meet Charles. Twice, in fact.

“There was quite a lineup of students and other members of the public on each side of [the walkway], so I just kind of edged my way to the entrance and stuck out my arm and asked [Charles] if he would mind signing my cast.”

A receiving line was formed and the prince spoke briefly with all in attendance. Charles was smaller than Ms. Harrison expected (“except for his ears”). “I expected a much more intimidating person,” she says.

She told him she was studying English literature, and the prince admitted he knew less about her major than he probably should, given the job he would inherit.

Dr. Overall, now emerita, would later write in the Kingston Whig-Standard that when she told the future king she taught philosophy, he turned serious, expounding on the importance of teaching young people about ancient philosophers.

“As an instructor of contemporary feminist philosophy and biomedical ethics, I was at a loss to explain, in a short conversation, why I don’t teach Plato,” Professor Overall wrote. “I sensed that the prince mildly disapproved.”

When the last guests had received their audience, Ms. Harrison recalls, “we were all kind of just milling around and he was still there, so they … made a line again and everybody went through it all over again.”

After about three-quarters of an hour of small talk, the prince took his leave. His visit to Queen’s might have ended then, but for Charles’ insistence on seeing an exhibit at the Agnes Etherington Arts Centre, where drawings by London-based architect Léon Krier were on display. Mr. Krier shared the prince’s disdain for modernist architecture and, three years before the visit to Queen’s, had been named master planner of Poundbury, Charles’ experimental community in Dorset, England. The prince deemed the exhibit “magnificent,” the Whig-Standard would report.

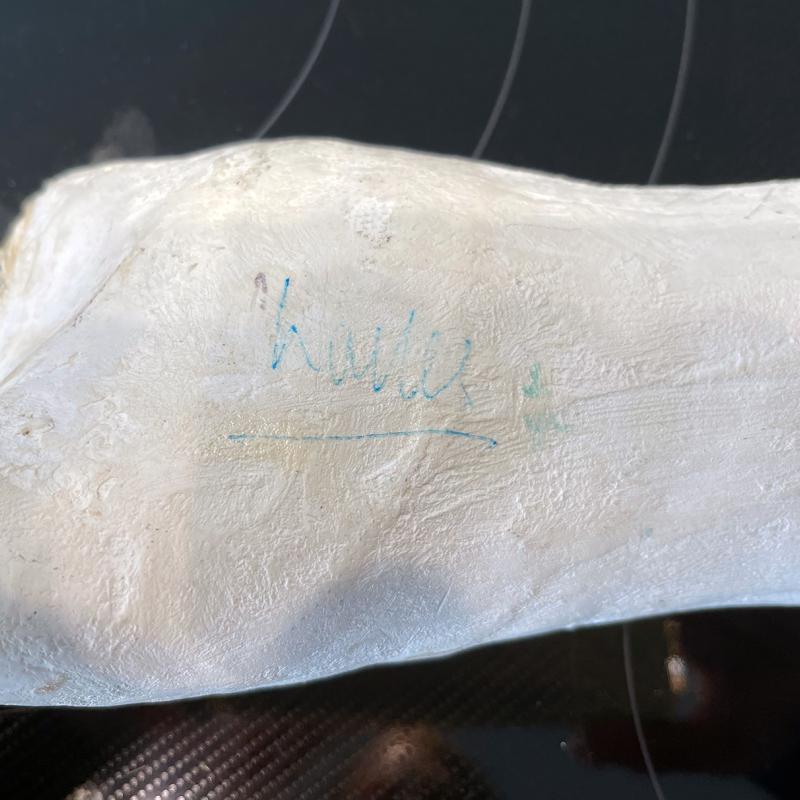

As he left the arts centre, a chance encounter with Sharon Tysick, Law’96, would leave the future Crown attorney for the district of Nipissing with a souvenir she has kept ever since.

Ms. Tysick was walking from class when she happened on the crowd outside the Agnes Etherington Art Centre and realized what it meant. She looked down at her left arm, encased in fresh, white plaster, and made a spontaneous decision. She had been struck by a car while bicycling the previous week, and she saw an opportunity to make something good of the mishap.

“There was quite a lineup of students and other members of the public on each side of [the walkway], so I just kind of edged my way to the entrance and stuck out my arm and asked him if he would mind signing my cast,” Ms. Tysick recalls. The prince immediately agreed.

“He tried one pen and it wasn’t working and … he got another pen from security,” says Ms. Tysick. “He signed Charles, that’s all, just Charles.” Sometime later, a royal biographer would visit her to chronicle details of the encounter.

“I’ve kept [the cast] all this time, just kept the portion he signed when they cut it off me. It’s faded substantially over time.”

While other witnesses to the royal visit don’t have physical mementos, they have a good deal of memories that have resurfaced since the prince became King.

“I had always thought of [Prince Charles] as kind of a cold and distant person, especially after how the news had been depicting him in comparison to Diana,” says Ms. Harrison. But in fact, she says, Charles was “warm, sweet, soft-spoken, but impish.”

Ms. Harrison would later read the prince’s convocation speech and be impressed, even more so when she eventually learned his marriage had been on the rocks at the time of his Queen’s visit. The speech, she says, “was just so hopeful at a time when his own life was kind of falling apart, and he was able to find that inspiration inside himself.”

Queen’s is a magnet for stimulating speakers, says Farah Mohamed, “because of … the popularity of the school, but also because it is a place of intellectual exploration. People came to speak there for the same reason people came to study there.”

“I saw lots of interesting people [speak] at Queen’s,” she says, “but the prince was at the top of the list.”