I just finished reading the stories of Dr. Anita Jack-Davies and Dr. Kate Kemplin in the latest edition of QAR. I’ve been reading the magazine for almost 40 years and I have never before been so profoundly touched, moved, and disturbed by any other articles in the magazine. As a white privileged female Canadian woman, I say to Dr. Jack-Davies: I’m so very sorry. I will do better. Thank you for your courage to tell us the truth. To Dr. Kate Kemplin, I say: your fortitude and commitment are awe-inspiring. Both of these women are phenomenal role models for women everywhere, but especially young women starting their university education. I am ever so grateful to the Review for delving into these stories and sharing them with us.

Mary Ellen (Lunney) Vice, Artsci/Ed’81

I usually do a casual read-through of each issue of the Queen’s Review, but this time I have slowed right down and am reading nearly everything. Thank you.

But why I am writing is because the combination of the Principal’s letter, the information about Black students not being admitted to Medicine between 1918 and 1965, and the article by Anita Jack-Davies has been a real wake-up call for me. Thank you to Principal Deane, the author of “Confronting Exclusion,” and Dr. Anita Jack-Davies.

I don’t live in the Kingston area, and don’t attend alumni events in Toronto either. But even with that level of non-involvement in the university, I would strongly support any actions towards “making choices for a more just, equitable, sustainable, and globally relevant future” for Queen’s.

Lorna Hilder Krawchuk, Arts’64

I want to take this opportunity to express my appreciation for the recent Alumni Review. It was without a doubt an excellent read! It was the very first time that I have read a Queen’s Alumni Review from cover to cover.

The context for this statement is that I have been receiving these magazines for decades and rarely read them, or I read an article or two. But this time, for some reason I took the time to read each and every article. Perhaps it was Principal Patrick Deane’s lead commentary on “The choices we make” that encouraged me to read further or perhaps it was the inviting cover of Dr. Anita Jack-Davies talking about race.

I do wish to say that Principal Deane’s final paragraph in his article which stated “we are the agents rather than the victims of history and therefore capable of making choices for a more just, equitable, sustainable, and globally relevant future” that really provided the springboard for my journey through the magazine.

Once again, thank you for a job well done. I look forward to reading more of the upcoming issues of the Queen’s Alumni Review.

Peter Vanderyagt, Arts’72

Thank you for this issue. I read it cover to cover and it is an emotional issue; powerful. I hope everyone reads it.

Lawrence Wardroper, Artsci’81

I would like to commend Dr. Anita Jack-Davies for her brave and stirring essay, “After the Fires Burn.” It was difficult to read, and crucially important. Being called out is an essential part of the process of unlearning ingrained racism, but calling people out is a risky act for BIPOC to undertake. Dr. Jack-Davies is courageously calling all of Queen’s out and asking us to do better, to make the university a truly welcoming space for all students and staff and to listen to and celebrate all the voices we members of the dominant culture have not made space for – that we have silenced, ignored, and disdained – in the past. We can only benefit from such changes.

I would like to recommend the workbook Me and White Supremacy by Layla F. Saad to all my fellow white alumni ready to do their part, do the work, and learn how to decentre themselves. It’s time for every single one of us to listen. To unlearn what we have been taught. To take responsibility for the people we have hurt and ignored and the harm that has been inflicted because we want to keep the power we are used to.

Let’s sit down. Let’s listen. Let’s do the work and let’s not stop doing the work. Let’s all honour Dr. Jack-Davies’ courage by doing better.

Cat London, Artsci’03

While very troubled by Dr. Anita Jack-Davies’ experiences in the Review’s last cover story, I disagree with her conclusions. I am a non-white alumnus who immigrated to Canada as a child in the 1970s. I am puzzled by the comment being “stuck in Canada” and the implication that it is a sentence of misery. Canada is a beacon of hope in the world, a shining but not perfect example of what a free people, living in a just, democratic, tolerant, pluralistic society all can accomplish, individually and collectively. Though racism I have faced has driven me to tears, I feel truly blessed to be “stuck in Canada.”

I too am sometimes confused with others of the same race and gender, not by racists but by people genuinely mistaking me for someone else. There is no evidence supporting Dr. Jack-Davies’ suggestion of deliberate racism in the cases she cites, nor why similar situations are “racist micro-aggressions, micro-insults and micro-invalidations.”

The author recounts being made to feel she had “nothing to contribute” to a conversation two white colleagues were having. There is no evidence that exclusion was based on race either. In my life, including at Queen’s, I have encountered similar situations; sometimes the other individuals were white, sometimes not. As an introverted, shy, reserved guy, social interactions are always difficult and sometimes lead to exclusion. But not because of my race.

Understanding our interactions with others solely through the prism of race is a narrow, tribalistic world view that, as history shows, is a recipe for anger, resentment, paranoia, and grievance. It stifles necessary constructive dialogue between people of different perspectives, isolates us from each other, and leads to the breakdown of civil society.

Non-white Canadians are not a monolith; we don’t all see the world through the confining perspective of race, demanding our grievances be addressed because of the primacy of our lived experience. Our views are as varied as our skin tones, our ancestries, and the diverse cacophony of our accents. Any decision Queen’s administration makes on issues of race must recognize this diversity of perspectives.

Jawhar (Jor) Kassam, Artsci’95

I would like to thank Dr. Anita Jack-Davies for her brave and important writing on her experience within the Canadian academic context. I have been reading the Queen's Alumni Review for 50 years and this is one of the two most important articles I have read in it. The other one was on surveillance by corporations, which we all know about now, but didn't at the time. On an artistic note I can't help but mention the excellent photography [by Bernard Clark] accompanying Dr. Jack-Davies’ important story. The whole article was so well done. Thanks for having a first-person account of racism featured in the Review and to Dr. Jack-Davies for sharing her experiences with us.

Susan Lawrence, Arts’70, Ed’75

Congratulations to Dr. Jack-Davies for providing an article that so caught my attention given the timing in our world’s history that I read and re-read her entire story several times. My interest in what she had to say was piqued when she challenged the reader to “feel unsettled and stirred.”

For me, her goal was achieved but possibly not in the way she meant. I have endured witnessing death before George Floyd. Murder is never fair because it is the loss of a life without a fair hearing. It does not matter who it is or what they look like.

Racism. An ugly word. To be left out of the dictionary only in a utopian environment. In reality, I fear, because we are all human, it will always be with us somewhere and to different degrees. There will always be the reality of “I am better” or “You don’t belong here” or “You are different” or “You are a minority.” I have endured all of these.

Racism. Was police brutality really the spark or simply one man’s racial attitude that exploded at a time and a place that was caught on video. My response to your article is not to diminish what you are saying but rather to put it into my perspective – an alumnus from whom you asked for a response.

My experience at Queen’s was one that provided me with some life experience, some life skills, and a degree that simply stated I successfully completed four years of study. My experience while there was determined by me and how much I wished to participate or not. Just as in my work life that followed, I had to work hard for success and learned that it was often up to me to decide how my experience went. But not always.

I only experienced real prejudice when I entered the workforce. It was because of my colour that people demeaned me; isolated me; swore at me; spat on me; assaulted me; and tried to kill me. My wife and family never knew if I would return home from a day at work. I always feared for the safety of both my brothers and my sisters.

As you might already have guessed, my colour is blue. My job’s focus is to protect you.

Whether on campus or around the world, talking about, and trying to become better at, eliminating racism is a good thing. I wish all success to you as the University Council’s first EDII adviser. All that I would ask is that your focus include more than one colour.

Michael Gilbert, Artsci’77

Remembering Dr. Atherton

Professor David Atherton (Engineering Physics) died March 18.

I had Dr. Atherton for physics in first-year engineering. He would always instruct us to “draw a large free-body diagram. It must be larger than my thumb, and I have a very large thumb.” And, indeed, he would walk around class looking at our diagrams and flatten his rather large thumb onto our notebooks to see if it covered the diagram. If it did, you had to draw a larger diagram! To this day, my Sc’91 friends and I who took that class will regularly break out into an imitation of Dr Atherton’s free-body diagram instructions, in our best British accents of course! We remember him fondly.

Debbie Gray, Sc’91

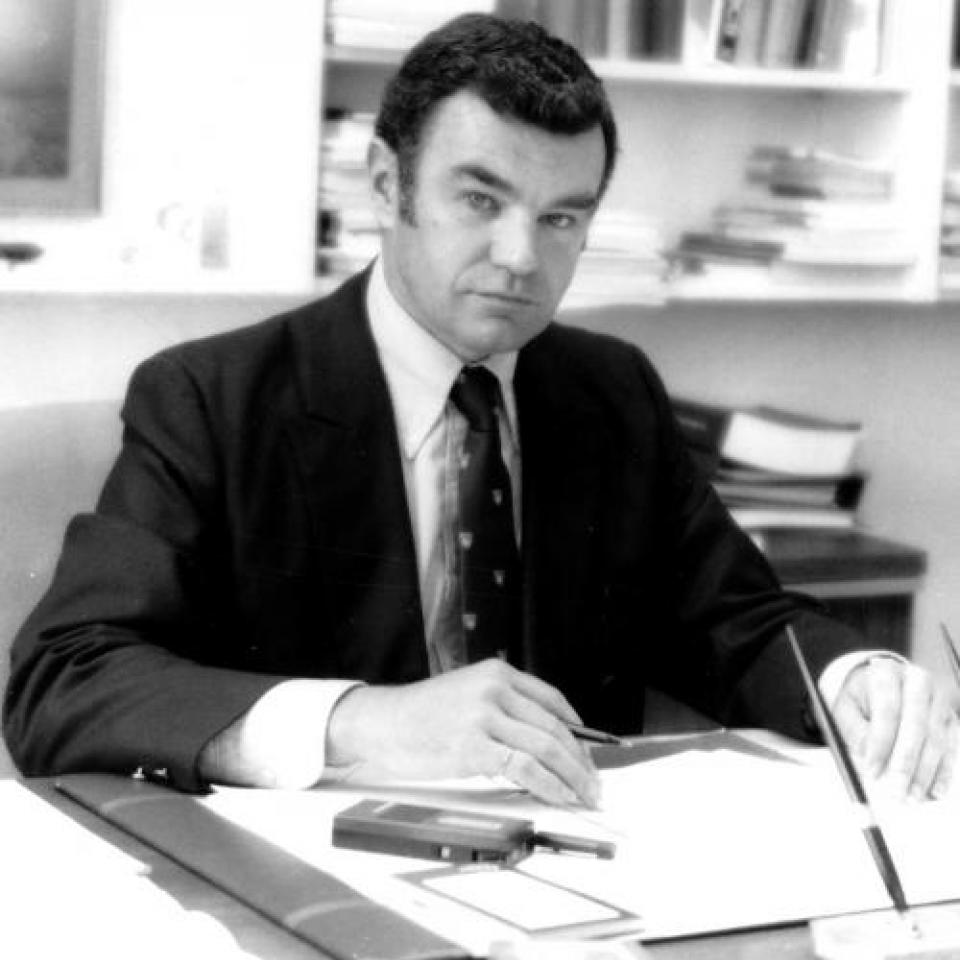

Remembering Dr. Gordon

Professor Emeritus and former Dean (Business) John Gordon died April 27.

I first met John Gordon early in 1983. I was applying to the MBA program and I wanted to do a thesis on technology transfer between universities and industry. He agreed to meet me despite his very busy schedule teaching, doing research, and serving as dean of the business school. He embraced the proposed study enthusiastically and he and Professor Peter Richardson agreed that they would guide my work.

I soon learned that the warm welcome I had received was typical of Dean Gordon’s interaction with students. In fact, if I had to describe his philosophy in just three words they would be these: Putting Students First. John taught Operations Management to the MBA students. He was always extremely well prepared, insightful, and engaging. If a student wasn’t grasping a concept, he would find another way to explain it. Somehow, in addition to all of this, he made his classes fun. His sense of humour was always present and a smile came easily to his face.

With John’s support we secured funding from the Ministry of Industry for my research study. We visited technology transfer organizations at other universities and learned about what worked and what didn’t. We reported our findings to the Ministry of Industry, and they were used to redesign the technology transfer office at Queen’s. John had a talent for seeing possibilities and making things happen. He used his time and energy in ways that ensured they had maximum impact. I learned a great deal from observing how he worked.

Twenty-five years later, John welcomed me back to Queen’s Business School as Executive-in-Residence. It was amazing to see the same spark and smile I had first experienced in 1983. John will be missed greatly, but his tremendous spirit lives on at Queen’s today.

Hugh Helferty, Artsci’77, MBA’85, PhD (U of T)

We asked readers to send us their memories of distance and continuing education at Queen's.

I have a unique view of distance education at Queen’s during the years 1952 to 1955. The acting Director of Extension, Kathleen (Kaye) Healey, lived in the same house where I roomed. She was my girlfriend’s aunt which meant that I was often extended hospitality. One year, it became my work to accompany Kaye grocery shopping as chief porter. I did other chores around the house as there was

no other male available to do them; not that Kaye was unable, but her other duties were heavy. Besides, I knew that if I pleased the aunt, the niece would look on me kindly. And the frequent meals I was served helped me stretch a very small budget.

The impressive thing I witnessed about the work of the Extension Office was not so much getting course materials out to extramural students living far away but organizing the examinations. Exams were timed for late August to coincide with summer school examinations and supplemental examinations for intramural undergraduates who had failed a course and were accepted for a second chance.

Kaye would often come home late for supper carrying a huge stack of files and a dictation machine. While I was chatting with Kaye’s mother, who suffered gravely from arthritis, Kaye would dictate letters. One would be to a Theology alumnus asking him to proctor exams in his home in South Africa. Another asked an Engineering grad to set up an exam centre in Whitehorse. She mined the alumni records for reliable proctors for remote examinations all over the Commonwealth and beyond. Then there were letters to students establishing and confirming exam arrangements. Hundreds of letters. The exam papers and return answer books all had to be securely shipped in time.

It was a huge operation and typical of Queen’s in that time to deny the title of director to a woman doing the work but without academic credentials. Eventually, Dr. Wes Curran, formerly of Biology, took over as director. A grateful Summer School Association made a special presentation to Kaye Healey and the university conferred on her an honorary Master of Arts. One of the Houses in Jean Royce Hall is named for her.

Many alumni, particularly teachers gaining first degrees, have benefited from the meticulous hard work of this woman.

Bert Horwood, Arts’55, MSc’60

You were asking for examples of “continuing or distance education.” One instance was that of my father, D. James Macdonnell, BA 1932, MA 1933.

The third generation of his family to attend Queen’s, he enrolled at Queen’s in the autumn of 1925 but contracted polio in the summer of 1927, leaving his legs totally paralyzed for the rest of his life. In those days before physiotherapy was generally known, he was confined to bed at home in Ottawa for almost three years, with the result that all his leg muscles completely atrophied.

In spite of this difficulty, however, he completed his Queen’s BA by correspondence, and went on to do an MA; he told me that he was the first person who was allowed by Queen’s to do a post-graduate degree by correspondence.

He was, however, required to do a six-week summer term in Kingston to finish his MA after his thesis was written and accepted, and he often described how, for his course in Greek, he was forced to climb, using his two crutches and with heavy steel braces on both his legs, the many steps to the second floor of the Old Arts Building, although there was an available lecture room on the ground floor to which the class could have been moved. (But I have often observed – I myself walk now only with a four-wheeled walker – that people who walk with difficulty or sit in wheelchairs are relatively invisible to those around them.)

On the other hand, my father greatly enjoyed his whole university experience and happily encouraged his children to attend Queen’s!

Frances Macdonnell, Arts’69