It’s the end of May. Kate Kemplin is sitting in a hotel room near Windsor, Ontario. She’s self-isolating for 14 days after spending two months on the COVID-19 healthcare frontline in New York City. Two months of brutally long days, setting up protocols, developing practice guidelines, and caring for patients in a giant enclosed “bubble” on a soccer field at Columbia University’s campus. All so that she and other former military health-care personnel could take some of the strain off New York’s overwhelmed hospital system,which saw more than 72,000 patients with COVID-19 by the first week of April.

Kate can’t see her kids yet: they don’t even know she’s back home in Canada. “It would be mayhem!” she says, if her son, age 4, and daughters, 10 and 13, knew their mom was so close but still unavailable. But she’ll be home soon.

And besides, these are resilient kids: they’re Army kids. They’ve always known a world with one parent being deployed away from home for extended periods of time. And on top of that, their mom is a nurse. And they know that nurses are badasses who get things done.

Here are three and a half chapters in the life of Kate Kemplin: trauma specialist, researcher, professor, and badass nurse.

Chapter One

It’s 1997. Kate, born in Canada and raised in the States, arrives in Kingston to begin nursing school. She is 17 years old."My childhood was…complex,” she says. “I was – and still am – awkward socially and was lacking a lot of life skills. Before coming to Queen’s, I was able to skate academically. Not here. I wasn’t the best student in Nursing, which, as I recall, then had 66 per cent attrition rate from the first year to graduation.

“First year was a gauntlet – core courses in biochem, anatomy, philosophy, physiology – most were taken with pre-med and other health sci students. They all kicked me in the teeth. None of our courses were watered down for nursing. This profoundly shaped my view of my profession as a serious and important one. Never have I felt that I am ‘just a nurse’ or academically unequal to physicians. I had to fight for every point in every grade in almost every course. Clinically, I was sound – I felt at home in hospital and taking care of patients. Professor Cheryl Pulling supervised my first dressing change. Unbeknownst to us, the patient’s wound was actually open-chest – to their sternum – and very complicated. She said that I turned every shade of grey changing the dressing, but I nailed it.”

With the help of classmates and housemates, Kate started to build new skills. “Julie Lorenzin (Artsci'98, NSc'01) and I didn’t cross paths initially,” says Kate. “She was a front-row keener and I was the kid in the back row wearing pajama pants.” But they clicked: “Julie taught me to be a scholar and I think I coaxed out her inner rebel,” says Kate, who is still close with Julie, now a nurse practitioner in London, Ont.

But Kate was still struggling.

“Theoretical courses were painfully nebulous for me,” she says. “But in third year, my statistics professor astutely referred me for a full neurocognitive testing battery because I was bombing her course. I was so conditioned to being ashamed of my flaws that being diagnosed with disabilities was devastating. I tried to speak of them once to an immediate family member and the mockery was both unsurprising and unimaginable. So I hid them for years, even though logically, I knew they were neurological and not behavioural in origin.

“Queen’s was a great equalizer for me because everybody was the smartest kid in the room. I think I learned there how to struggle with being average in comparison, and how to persevere. That said: I’m white. I didn’t have structural or historical obstacles stacked against me, nor did I have to swim against the ostracizing tide of Queen’s lack of diversity. I grew up in theAmerican south and distinctly recall how eerily white Queen’s was – and still is. So ‘struggle’ and ‘persevere’ are relative terms when evoked by someone with my racial privilege.”

Kate graduated from Queen’s Nursing in 2001 and returned to the States. She wasn’t sure where she was going next, either in life or in her nascent career. But that September, she figured out her next move.

“When the World Trade Center was attacked, people were dropping what they were doing and heading to New York. A friend of a friend was working for FEMA. He was in our hometown visiting and was heading back to New York.” Kate decided to go with him. She was a nurse and nurses would be needed. Somehow, she could help.

All planes were grounded, so they drove 20 hours to get to Manhattan.

“We crossed the Bayonne Bridge on September 12th and could see the financial district from that height. It was so dark. We could see the lower tip of Manhattan, and it was a void: a black pit, with smoke coming out of it. There were lights in other parts of the city, but none there – except for spotlights.

“My hub was Moran’s Bar and Grill at the North Cove marina, a short walk west of the site through the Winter Garden Atrium. On my third day there, an FDNY chief seconded me to be medical support to their special operations/dive team living on the Firefighter, a massive fireboat pumping water from the Hudson River into the Trade Center fire. For a few weeks I worked and lived with them.”

At first, she stayed on the Firefighter, ready to provide medical treatment to the crew if needed. Kate was easily 20 years younger than any of the guys on the crew. She reminded some of them of their daughter, others of their niece or kid sister. One of them gave her a hard time, saying, “What are you here for, just to sit on the boat and make it smell nice?” Kate pushed back. “Listen,” she remembers saying. “I’m not just here to look pretty.I play rugby. I can take a hit.” Unspoken were the words: “I’m a nurse. I’m not scared.”

Kate earned their respect. This feisty kid, right out of university, had showed up. She didn’t know what she would be facing, where her skills would be needed, what would be asked of her. But like any one of the first responders, Kate went straight to the hotspot, ready to face the unimaginable disaster that was 9/11.

Kate accompanied firefighters to the pit, the deep smouldering emptiness that was what remained of the Twin Towers. At first, she stood at the edge of the pit, masked and suited up, and watched her crew disappear underground. Later, she went with them, wearing a safety harness and PPE as they did. She remembers climbing twisted girders that once held up skyscrapers. She doesn’t go into detail about what she saw there. She says simply, “I returned home just after my 22nd birthday that October.”

Looking back now, she says, “I sometimes think about my 21-year-old hubris: who thinks that they can just go to New York and do something meaningful there? Who really has that kind of arrogance?” She pauses. “But I don’t even know if it’s arrogance. I think it was just faith that I had the background and the training…and the backbone.”

But when Kate left New York, she found herself unable to fit comfortably back into normal life. She started working at a hospital, but once again, she found herself at odds with her surroundings. Working on a safe, clean hospital floor so soon after being at the pit seemed surreal to her.

“I found it extremely hard to relate to co-workers – and even patients – who hadn’t been affected personally by terrorism. For the life of me, I could not understand their perspectives – how could anyone complain about anything during that time? They weren’t burned alive or forced to jump from a skyscraper. They didn’t wake up one morning as usual and were violently widowed by lunchtime.

“I was really an island unto myself,” she says ruefully, “intolerant and out-of-place. I was going to change careers…and then I rotated to the emergency department and found my people. It’s still the only professional environment in which I feel completely at home.”

Once again, someone in Kate’s network reached out to her, and she seized the opportunity to make a change in her life, to make a difference.

Chapter Two

"Firefighters I had gelled with in New York lived about an hour from the city and a couple of them cajoled me into moving to that area.”

Kate began working as a nurse again, this time in a large emergency department in a busy rural hospital. There, she met a handsome young soldier home between Army assignments.

“With more emotion than reason, I married him and started to build my career at whatever duty station we were assigned to.” Balancing her work as a civilian nurse for the U.S. Army, Kate also started a master’s degree in nursing at Loyola University in New Orleans. Just after she had been accepted in the program, her husband Michael was transferred to a base in Germany.

The years went by. Kate and Michael welcomed their first daughter, and then their second. As a trauma and emergency nurse specialist, Kate had treated a wide variety of medical issues and injuries, most of which were familiar. But there was something new emerging in her patients, something she hadn’t come across before.

“Around 2006, I noticed soldiers who’d deployed to the Middle East were presenting clinically with non-specific issues: disordered sleep, inexplicable anger, headaches, memory loss, relationship dysfunction. Every single one of them had blast exposure – often repetitively – while deployed, but no previous history of head injury or significant psychological abnormalities."

Intrigued by this new phenomenon, Kate shifted the focus of her graduate studies at Loyola to combat-related traumatic brain injury.

Traumatic brain injury – TBI – occurs after a sudden trauma or blow to the head disrupts the function of the brain. Most of us are aware of the potential for concussion from a fall or sports injury. A concussion is medically classified as a TBI. But it is not necessary to have been physically hit to experience a traumatic brain injury. Blast exposure – close proximity of a person to an explosion – can damage the brain significantly from crushing air pressures. Blast waves can create microscopic tears in the tissue and blood vessels in the brain, with serious consequences. The phenomenon of “shell shock” documented in soldiers in the First World War, once classified as a neurosis or psychological shock from the horrors of war, is now considered to be traumatic brain injury caused by proximity to artillery fire and explosives.

Kate threw herself into her graduate work, focusing her research on “mild” TBI – “mild” being a clinical term she loathes – and injuries sustained from blast exposure. She developed data sets and extrapolated projected clinical findings.

And then her work came close to home.

Michael was deployed to Iraq. “In December 2007, an explosive-formed penetrator – a bomb designed specifically to penetrate armor – detonated under the seat of my husband’s vehicle when they drove over and triggered buried sensors.” Michael walked away from the explosion without a scratch.

“Michael was physically intact,” says Kate, “but soldiers in the same vehicle had detached retinas and were bleeding from their ears and noses.”

Her husband returned to duty within 12 hours.

“I knew his regiment’s physician professionally,” says Kate, “and I remember sending him an email saying, ‘I know just enough about TBI to be a real pain in your ass about this.'

“But, back then the attitude – which, honestly, still persists now – was very dismissive. Unless you were physically injured enough to warrant evacuation to Landstuhl [a U.S.-run military medical centre], soldiers maybe got a night’s sleep and then went back to the mission without neurological rest or treatment. Based on what we are seeing now, that practice could prove fatal to many soldiers down the line.”

Michael finished his deployment and came home. But he wasn’t Michael anymore.

“It was like watching my graduate studies of TBI unfold before my eyes: every trope about TBI affecting personality, function, and relationships was happening inside my own home. It was exacerbating my shortcomings and exposing my worst qualities as well. Everything was disrupted.”

Kate tried to get professional help for her husband. She knew what was happening to him: she knew the science and, as a nurse, she had the inside connections. But she also knew what she was up against.

“Many soldiers will neither seek nor accept help for neurological injuries, because those usually manifest in aberrant behaviour. So getting help for what soldiers perceive as personal shortcomings is often professional hara-kiri,” she says soberly, “despite all the platitudes of support from military public relations outlets. To this day, speaking out can be career-ending. There was a general who spoke publicly about his struggles a year or so ago. He was immediately ostracized by his peers and the military. A general. Now imagine enlisted soldiers trying to fight against that pervasive stigma.

“That said,” she continues, “retired generals like Gen. Peter Chiarelli put their money where their mouths were and moved the needle on TBI. When I was contracted to develop data capture for the Department of Defense, I was asked by my boss to draft policy and ‘pretend it’s going to the White House.’”

“Sir…is it going to the White House?” Kate asked him. She didn’t get a direct answer, just a deadline from her boss before he hung up the phone. But shortly thereafter, on Aug. 31, 2012, President Barack Obama issued an Executive Order titled “Improving Access to Mental Health Services for Veterans, Service Members, and Military Families.”

“About three bullet points and five sentences in that Executive Order may have originated from me,” says Kate. “Nursing science possibly influencing national policy, even within one paragraph? I’ll take it.”

At home, Kate was fighting hard for – and with – Michael, who was still being deployed even as his mental health deteriorated. “I barked up trees and called in favours from command psychiatrists and other medical colleagues who agreed to see and treat Michael off the record. But he had top-level security clearances to protect, and he refused to go to appointments for fear of future polygraphs and mission-specific vetting of his medical history.”

Michael went on six more deployments with the U.S. Army.

“I pushed unsuccessfully for years,” says Kate now, “and ultimately decided I was the only one I could treat or change. I accepted defeat and filed for divorce three weeks after my doctoral defence in 2013. I had two young girls and the prospect of repeating history by raising them amidst dysfunction and conflict hit too close to home; it was unthinkable, no matter how much love and dedication remained in the relationship.”

According to the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center has reported nearly 350,000 incident diagnoses of TBI in the U.S. military since 2000. Among those deployed, estimated rates of probable TBI range from 11 to 23 per cent. In Special Operations Forces (SOF) like the Green Berets, Navy SEALs, and clandestine units, the incidence is likely much higher: they sustain 83 per cent of combat fatalities and deploy more often and repetitively than conventional forces. And SOF members die by suicide at much higher rates than other military populations.

“I think there’s some mechanism to overachieve,” Kate says now. She’s speaking of both Special Operations Forces and nurses like herself. “Especially those of us with thorny pasts: we need to prove we can reach the mountaintop.” She had just finished a clinically focused doctorate at Loyola University studying SOF medics’ care of combat casualties, but “I was annoyed by its limitations. I was told I’d never independently add to the body of knowledge. I wasn’t prepared at that point to independently lead research endeavours, so I then started a research science PhD at Rush University in Chicago, intending to study clinical cognition in military members.

“As my friendships and collaborations with SOF service members grew and deepened, I started to lose them to suicide. First, the hockey player who taught my eldest daughter to skate at Fort Bragg, Army Green Beret Michael Mantenuto [who starred in the Disney hockey movie Miracle] died by suicide in April 2017. Within a day of his death, a Navy SEAL friend’s junior medic, Ryan Larkin, died by suicide. Three years into my PhD, with a year off to have a baby, I reversed course and decided to study resilience and suicide in Special Operations, who are assumed to have the highest resilience but are dying by suicide at three times the rate of conventional military populations.”

It’s June 2019. Kate wakes up on a beautiful Sunday morning. She is on faculty at the University of Tennessee in Chattanooga. Three weeks earlier, she had published her initial findings about resilience and suicide in Special Operations Forces: the first nurse to tackle those topics in that population. She checks her email automatically, as tenure-track junior faculty are compelled to do. There is, unexpectedly, an email from Michael, her ex-husband. Since their divorce, their communications had become fraught. Six years later, they have both moved on. Kate has a new husband, Ben; another child; a new academic career. Cautiously, she opens the email from Michael.

She reads the first sentences, and falls to her knees, gasping. You’re experiencing tachycardia, her brain tells her. Move, says her brain. Think.

“I knew where he lived, and years spent in emergency medicine enabled me to deduce to which trauma centre he would have been flown. I called the charge nurse line at R. Adams Cowley Shock Trauma in Baltimore, after speaking with Michael’s mother and brother.”

Things moved quickly. Kate moved quickly.

“Emergency nurses are mafia-esque in taking care of their own,” says Kate wryly, “and this was no exception, even though they didn’t know me personally. They put the phone next to Michael’s ear before transferring him to intensive care, and I was able to tell him to hang on, that I was on my way. Gone was the bullshit we’d put each other through – everything superfluous falls away when a one-sided conversation occurs with the hum of a ventilator and squawks of monitors in the background. I got off the phone, grabbed my go bag, and assured Ben I’d be home soon and safely.

“The drive from Chattanooga to Baltimore should take ten hours at minimum. Living in Germany among autobahns trained me well; I arrived in under eight. Members of our Army family spoke to me through Bluetooth as I pushed my turbodiesel to its limits through Appalachia. ‘Michael never came back from Iraq,’ said one friend to me. ‘He never landed.’

“When I walked into the neurotrauma ICU, monitor readings were grim. Intuitively, I noted about a dozen vasoactive and sedative drips and their infusion rates, vital signs, and ventilator settings – and Michael himself.

“Patients’ families have told me – and millions of other nurses, I’m sure – that their loved one waited for them to arrive before dying, that they sensed a change when they walked in the room, that the patient ‘knew’ they were there. And most of the time, when I heard this, I would nod compassionately and evoke some semblance of therapeutic communication while I kept their loved one clinically stable. Yes, unconscious patients can hear you, even when heavily sedated. But I usually put more stock in quantitative data and clinical assessment than feelings. Michael’s injuries were incompatible with life and he was maxed out on every drip and vent setting. There was no clinical explanation for him still being alive.

“As I approached the father of my two girls and my first real young love, I kept one eye on the monitor mounted above his head. The energy in the room told me all was forgiven between us: the fights, the emotional fractures, me leaving him. As I spoke into his ear, his heart rate approached the low end of ‘way too high.’ His cardiac rhythm started to show detectable P-waves. His arterial blood pressure, too low for decent organ perfusion, rose. It was nighttime and we only had until morning, when surgeons would take him to the O.R. and harvest his organs.

“I did what Queen’s taught me to do in the start of second-year clinicals. While exercising incredible mastery of delivering the complicated calculus that is patient care, nurses restore patients, starting with attending to their dignity. It was Michael’s last night on Earth and as powerless as I was to fix anything else, as a Queen’s nurse I’d be damned if he wasn’t pristine in death. I loaded Michael’s favourites on my iPhone and turned the music up. Two nurses – two, in a busy major urban trauma ICU – stopped what they were doing when I asked for a wash basin and supplies. Without moving him and jeopardizing his intracranial pressure, we washed him head to toe. And then we hugged each other and cried.”

On the way home to Tennessee the next day, Kate got a phone call from Michael’s psychiatrist. He described to Kate a symptom constellation he had seen in Michael; that set of symptoms triggered a memory for Kate. “Dr. Dan Perl of Walter Reed/Uniformed Services University had found astroglial scarring in Ryan Larkin’s brain post-suicide and in other post-mortem brains from soldiers with chronic TBI who died by suicide. My apologies to the laboratory intern who answered the phone and heard me blurt out, ‘My ex-husband had TBI from combat and died by suicide yesterday and you have to go get his brain and analyze it.’ But by golly, Stacey Gentile of the Center for Neuroregenerative Medicine activated an incredibly compassionate organ harvesting team who made it happen.”

Chapter Three

It’s March 2020. Kate has moved back to Canada with Ben and their children. She has accepted a position at the University of Windsor. She’ll be teaching research methods and quantitative statistics, to both undergrads and PhD students. She’s looking forward to it: she loved teaching research in Tennessee. As a professor, she upholds the rigorous standards embodied by her Queen’s nursing profs. She also infuses her teaching practice with self-effacing encouragement, remembering her own academic battles as an undergrad. “Students often – and incorrectly – think professors have done everything right the first time. When I have students who are struggling, I offer to show them my transcript from Queen’s, because how you start out doesn’t dictate how you end up.”

School starts again in September. Kate is looking forward to the summer to hang out with the kids and settle into their new neighbourhood.

And then COVID-19 hits. It hits New York City particularly hard.

“When New York started to deteriorate under the strain of this virus, I knew I’d be going back there in some capacity. It was just a gut feeling. I started prepping the kids at the end of March, saying, ‘You know, I’m probably going to have to go help there. I’m probably going to have to go help people. I’m a nurse, and this is what nurses do.’”

Once again, someone in Kate’s network reached out to her, and Kate was ready to show up. “Missy Givens and I had worked together in emergency medicine at Madigan Army Medical Center about 15 years ago. I later learned that I was her charge nurse on her first night shift as an attending.”

Colonel Melissa Givens, MD, MPH (“Missy”, to Kate) had recently retired as an emergency room physician with the U.S. military. She and Kate saw what was unfolding in New York: its health-care system was buckling under the weight of COVID-19, and they were compelled to act. Missy and Kate put together a team of six and started videoconferencing daily about developing larger teams of highly trained former SOF medics to head to New York to alleviate pressures on individual critical care units’ staff. Through colleagues, Missy learned that New York-Presbyterian (NYP) Hospital had a field hospital ready to handle patients with COVID-19, but no one to run or staff it.

“Missy called me and said, “I told [NYP] I could be medical director but would need a chief nursing officer. How do you feel about running a 220-bed field hospital?’ I tried to think of a nurse who’d worked with SOF medics, studied their practices and philosophy, knew their clinical capabilities, who would be willing to drop everything to work and live in a pandemic epicentre…It dawned on me that I was that nurse. So I grabbed one of the kids’ hockey bags, packed it with clothes, tossed it in the car, and started driving.”

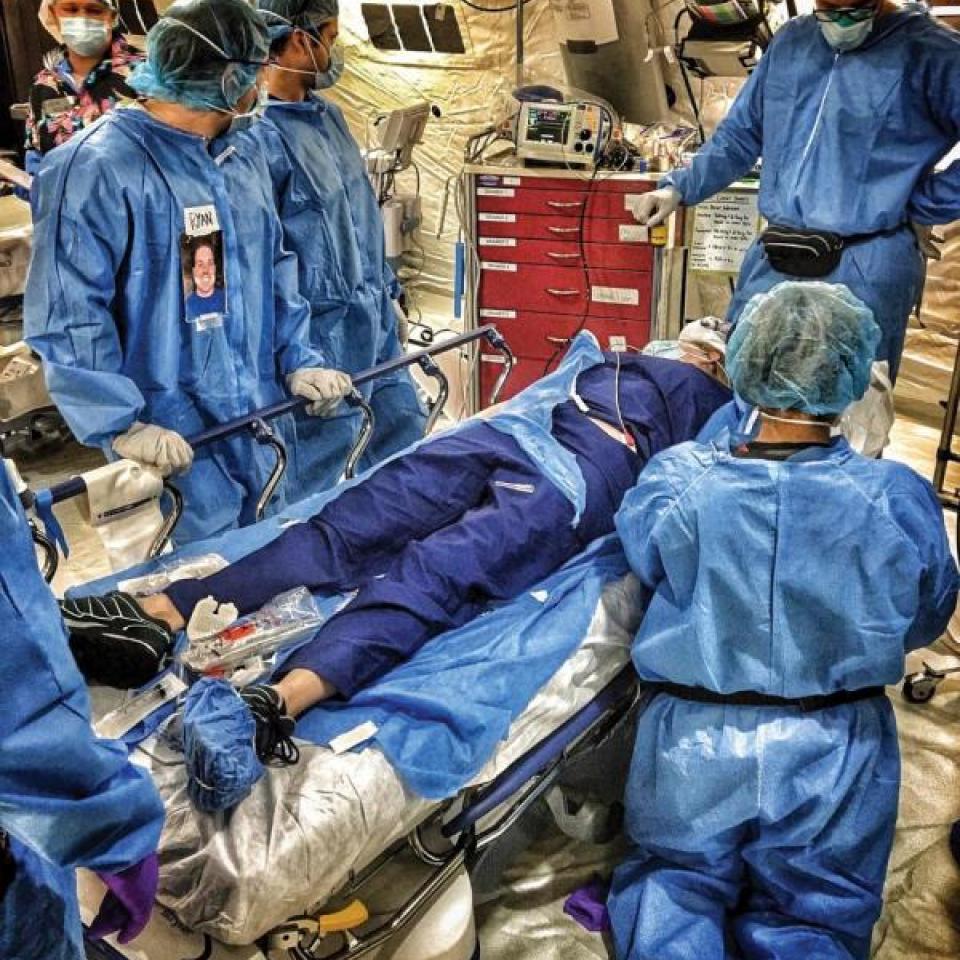

Working in the bubble

Close to Columbia/New York-Presbyterian’s Allen Hospital is “the bubble,” a tented soccer field belonging to Columbia University Athletics. Kate and her advance team were responsible for turning it into a functional hospital for patients with COVID-19. “I ultimately had responsibility for about 130 people, both civilian nurses and Special Operations medics functioning as nurse equivalents in their assigned roles,” she says. “All the medics assigned to specific clinical roles – who were already the best-trained in the military – had undergone additional training in prolonged field care, which had prepared them to provide nursing-equivalent critical care in circumstances where you can’t evacuate casualties. Ironically, I was part of the initial efforts that developed prolonged field care during its inception, and I was now seeing it applied to a pandemic.

“These medics are also used to deploying out of the back of a truck or in a really remote village. So when they walked into the bubble, it’s bright, it’s shiny, there’s linoleum, there’s electricity, there’s oxygen, so they were like, ‘Wow, this is like the Ritz.’”

Prior-service military personnel were also well-trained in suiting up in protective equipment, essential for treating patients with COVID-19.

“In developing PPE procedures, we assumed airborne transmission, based on reports from overseas and so we implemented really strict protocols for being in the bubble. At all times, you had to cover your hair, you had to wear eye protection, you had to wear a surgical mask over your N95, and don what we called the bunny suit and shoe covers and two pairs of gloves and all these other layers. Head-to-toe PPE. And the medics were just like, ‘Okay, no problem.’ To my knowledge, none of our staff contracted COVID-19 from working at the field hospital.

“The days were really long. In the beginning weeks, I’m pretty sure we did sixteen 16-hour days straight. It was just very, very intense. Opening a hospital typically takes years; we did it in six days, with personnel from all over the country with vastly different backgrounds. Prior to putting our leadership team together, I contacted Amanda Brandon - a really fantastic mental health practitioner and colleague familiar with the Special Operations community and expert in treating traumatic stress. One of my first actions was hiring her to be the mental health lead for the staff. She was absolutely crucial because we anticipated what the stress and the strain could be, going in. I don’t see how we could have pulled this off without her. Just being able to have a quick hallway consult if you had a challenging meeting or needed to talk to someone about something sensitive....It was amazing to have a dedicated person there to ground you and help you talk through things, even if you were just having a rough day.”

The bubble gets a name

“When Missy broached naming the hospital, I thought, why don’t we name it after Ryan Larkin? Because in our academic community for Special Operations medicine, most people knew who Ryan was, and how he died. Because he was a medic, his death hit very close to home. He was such a caregiver and really compassionate guy. I reached out to Ryan’s parents whom I knew because we are part of this club that nobody wants to belong to: military family members who’ve died by suicide. His parents are very private, but were enthusiastic to name the hospital after Ryan.Inadvertently, that sent out a bat signal – when you name a field hospital after a fallen Special Operations medic, everybody in that community intuits your mission.”

The Ryan Larkin Field Hospital treated patients from every borough in New York City. Special Ops training came in handy here, too. “Special Operations soldiers all have to learn, with a fair degree of fluency, a foreign language. Some learn French, some learn Spanish, some learn Russian or Korean. So we would be treating a patient from Eastern Europe and we had a medic fluent in Russian: he could speak a lot of different dialects. Others spoke Mandarin or Tagalog. I mean, it was kind of uncanny. When we really needed that kind of language service, these medics just came through.

“That’s at the heart of being a holistic caregiver,” says Kate. “The first thing is you have to speak to patients in their own language. Medics who’ve been to war, very tough and battle-hardened clinicians, were shaving patients’ faces and bathing them while providing top-notch care. You can’t teach that kind of patient-centred compassion. But it’s not surprising: these patients were separated from their family– like soldiers and military families often are – and military-adjacent people tend to treat others in the same boat as our de facto family, regardless of DNA.

“Patients were actually surprised that we interacted so closely with them, or when we spent prolonged amounts of time in proximity to them. Before transferring them to us, hospital staff didn’t initially know if our patients were COVID-19 positive or negative and had to take precautions of distance. Whereas we knew we were walking into a positive-pressure and completely COVID-positive patient care environment: all of our patients had COVID-19. So we were able to just get right up in there with our patients like normal, except that we were wearing all this protective gear.”

Sending patients home

“Because we were in a bubble, if you played music in one corner, every patient could hear it. We ordered a nautical bell, as an homage to Ryan, who was a Navy SEAL. In the Navy, when you’re done your tour on ship, you ring the bell three times.We had it engraved and hung on a platform. And whenever patients left, they got to ring the bell.

“And then when we closed the hospital, we rang the bell for the last time.”

The beginning of chapter four

It’s mid-July. Kate is out of quarantine, and back at home with her family. She’s also hard at work on her latest research. She and fellow Queen’s grad David Barbic (Artsci’02, MSc’04, Meds’08) are exploring moral injury and quality of life in emergency clinicians in the age of COVID-19. David is a professor of emergency medicine at UBC. “Emergency and critical care clinicians are viewed as typically very tough and unflappable regardless of traumas we witness and treat. That hyper-resilient and impermeable stereotype, similar to how people perceive Special Operations Forces, can invoke stigma in clinicians who are mentally struggling while caring for incredibly ill patients during a resource-devoid pandemic.

“The predicate for moral injury,” says Kate, “is a shock to your psyche or to your mores. It happens when you see things – or do things – within a certain context that chip away at your institutional trust, your belief system, your ability to make appropriate clinical and moral decisions. Physicians and nurses in the er already see the worst and the best in humanity. If you ever want to see which community is having an overdose crisis or a violent crime problem, stop in at your local emergency room. We’re the first people to see it.”

The same goes for patients with COVID-19. The additional strain – the moral injury – dealt to clinicians practising during the pandemic can occur from stressors at home, rationing care, practising without enough PPE, and witnessing leadership failures during the pandemic. Clinicians are often unable to do what they are meant to and trained to do during this pandemic. And it’s taking a toll on health-care workers.

“Moral injury has roots in the military, with regard to traumatic stress and negative health outcomes – including suicide. Dr. Lorna Breen, the ER director at the Allen Hospital supporting Ryan Larkin Field Hospital, died by suicide while we were in New York. Not only did she contract COVID-19 and likely suffered from its neurovascular after-effects, she reportedly felt powerless to save so many sick patients. Even without knowing her personally, that hit very close to home for all of us working at a field hospital named for a Navy SEAL who’d died by suicide, and for those of us otherwise affected by suicide.”

“In March before leaving for New York, I was matched with three amazing medical students from Western studying at the UWindsor campus who were interested in trauma research: Hailey Guertin, Kylie Suwary, and Matthew Bentley (Artsci’18). We launched an international study of emergency clinicians’ moral injury during the pandemic, which was only possible because of their incredible scholarship and dedication, and because David took the reins from Vancouver while I was in New York.” Currently, Kate and David are working on defence grant applications to further study moral injury with nurse scientist Audrey Steenbeek from Dalhousie.

Reflecting back on the first chapters of her life, Kate says,“You know, when I first went to New York, and I was 21, I helped in a very small way. Now, almost 20 years later, with some education and practice under my belt, I was able to go back to New York and help stand up a facility where hundreds of people could be part of the fight against COVID-19.

“Queen’s does, in essence, teach its students positive entitlement. By virtue of rigour, prestige, and tradition, Queen’s grads either have a place at the table or we’ll bring our own chair. So, whether I was 21 or 40, I knew I could contribute in situations of duress, while under stress, and I can enable other people to contribute, too.”

Dr. Kate Kemplin is many things. She has one hard-earned BNSc from Queen’s University. She also has an MSc in Nursing, and what she calls “an overabundance of doctoral education.” She’s been in the pit at the World Trade Center days after 9/11. She’s practised with military and civilian patients on two continents.

She is a professor. She is a researcher. She is a mother. She loves Led Zeppelin. She has bad days. She has neurocognitive disabilities. She has an innate need to rock the boat, to challenge the system. She is complex and flawed.

“We have to be flawless in providing patient care. Yet many people think you can’t be a nurse or a physician unless you’re personally flawless, which is ridiculous. Even during this pandemic, clinicians are still reluctant to seek professional care for their mental health, despite knowing that the mind needs as much attention as the rest of the body. And in my experience, patients prefer clinicians who are proficient professionally, but also human. It takes stability and opportunity to secure an education in health care. Many clinicians and academics may have limited experience with dysfunction, have not faced discrimination, been single parents, or been housing- or food-insecure. Those lived experiences may therefore be somewhat theoretical to current leaders in health care, absent more women, immigrants, and BIPOC in leadership roles. Regardless of our own experiences, we have to insulate and rally around colleagues, instead of isolating them, during times of struggle.”

So Kate Kemplin has a message for all those badass nurses-to-be, especially those students who think,

“I don’t get this course…I don’t fit in…Maybe I’m not good enough.”

She says, “I never believed successful people who said ‘I’ve failed as much as I’ve succeeded’ until I had some spectacular face-plants myself. When you push the envelope and take risks – whether by taking a new professional role, researching sensitive topics, or by challenging how things have always been done – some failure is likely. “Spit the dirt out, dust yourself off, and ignore the haters who will judge or discourage you. Keep going, because you usually have to take the leap before you can see the net below you. I still don’t know what I want to do when I grow up, but I know it’ll be quite the ride getting there."