On October 4, Drew Feustel and two colleagues came back to Earth. At 12:55 that morning, they had squeezed into the Soyuz MS-08 spacecraft. At around 3 am., the Soyuz undocked from the International Space Station. Three hours after that, at 6:51 am, the Soyuz began its de-orbit burn and plunged back into Earth’s atmosphere. It landed in a remote part of Kazakhstan at 7:44 am.

Landing itself was an adventure. Astronauts – used to months of microgravity – feel slammed into their seats when gravity forces reach three times Earth’s gravity or higher. They careen down into the soil so hard that crew members are trained to keep their mouths closed before impact, so nobody bites down on a tongue by accident. Sometimes the craft’s parachute gets caught in the wind and the capsule drags a few feet. It’s a lot to handle in a small space, where three people don’t get much more than a telephone booth’s worth of elbow room to perform the necessary launching and landing procedures. But this is what Drew Feustel trained for, spending countless hours in simulation so he could be ready for any emergency.

The big surprise was the emotion he felt upon reaching Earth.

“I was a little overwhelmed,” after the landing, he says simply. Somebody handed him a satellite phone as he sat on the plains a few feet away from his landing site in Dzhezkazgan. “My wife and kids were on the phone. I was tearing up. I could hear Indi [his wife] crying. All the cameras were on me. Luckily, they had handed me some sunglasses.” Shielding his sensitive eyes from the harsh sun, the glasses also helped him to regain his composure as he adjusted to his first minutes back on Earth after 197 days away.

Feustel says he was glad that he managed to pull everything together before he was whisked into a tent for the first of a series of tests. His initial challenge? To stay balanced and upright. Those first few moments on his feet were tough. Used to space shuttle flights only a couple of weeks long, after six months away from Earth, he found his legs weren’t cooperating with him.

Quickly, another problem surfaced. “I started dry-heaving into a plastic bag.” The thought popped into his head: “I wish I was in a space shuttle again!”

Decades before Drew Feustel made his first trip to space hundreds of kilometres above he Earth, he made a journey in the opposite direction – to a notable scientific observatory two kilometres below ground in a mine near Sudbury. As Arthur McDonald and his fellow astrophysicists at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SnO) studied the nature of neutrinos – work that would earn McDonald a 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics – Drew Feustel, a PhD student in Geological Sciences at Queen’s, worried more about the movements of the Earth. The underground facility provided a perfect venue to learn more about the structure of the ancient Canadian Shield rock surrounding the former working mine. After a seismic event or earthquake, Feustel tells the Review, “I looked at how intrinsic materials, cracks, and rock structure would affect the seismic wave itself.”

After graduating from Queen's, Feustel joined Kingston’s Engineering Seismology Group and for three years, helped install equipment in underground facilities across Eastern Canada and parts of the United States. Oil giant Exxon hired him next to oversee and develop their own seismic monitoring program across land and sea.

The hours were long, the conditions difficult. When you work underground, you accept you might be trapped there. If you get stuck, you know that you may have to share food with the colleague you were disagreeing with earlier in the day. You understand that your very survival requires teamwork with your crew, because nobody working alone can fix the issue.

It turned out to be perfect training for spaceflight. NASA asked Feustel in 2000 to join the astronaut corps. A few short years later, Feustel had his hands on another laboratory that uncovers the secrets of the universe: the Hubble Space Telescope. You may think fixing NASA’s famed orbiting observatory would be the peak of an astronaut’s career. But Drew Feustel was just getting started.

Feustel was only four years old when astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked upon the moon in 1969. In the next decade, anything seemed possible regarding spaceflight.NASA brashly advertised it would bring humans to Mars in the 1980s. Vast Earth-orbiting stations would host astronauts as a first stop on this two-year trip to the red planet. Colonies would spring up on the moon to provide resources and training for Mars explorers.

“I imagined that as I got older and became an adult, travelling in space was going to be fairly common, and something that we all did. So I grew up believing that I’ll be an astronaut just like these guys who were going to the moon,” Feustel once told NASA. He says now that he always followed his practical interests when deciding what to do next in life, but the thought of being an astronaut was always at the back of his mind.

As the Cold War cooled, however, the budgetary impetus for NASA’s push into space was frozen too. Luckily, it wasn’t a permanent pullback from space exploration. It was a retrenchment. NASA refocused its reduced resources on the space shuttle, which made 135 missions into space between 1981 and 2011. The shuttle made spaceflight more routine, helped astronauts practise spacewalks and satellite repairs and regular science experiments, and even brought the first Canadian astronauts into space in the 1980s and 1990s.

Then in 1998, very soon before Feustel came on board, NASA’s dreams of an Earth-orbiting space station finally coalesced with the creation of the International Space Station. Incredibly, the first two modules joining up in space were an American module and a Russian module, representing a collaboration between the former Cold War rivals. Also participating were more than a dozen other nations: Canada, Japan, and several countries across Europe.

So NASA was in an exciting phase as Feustel began his training with the astronaut corps. The space station was only two years old, astronauts were building it block by block with spacewalks, and flight opportunities were frequent and full of challenge. Feustel completed his two-year basic training in 2002 and began technical duties in the space shuttle and space station branches supporting missions – all a part of the process to bring him to spaceflight in a few short years.

But he had to wait longer than expected. Everything stopped cold in early 2003 when the returning Columbia space shuttle broke up during reentry, killing seven astronauts on board. NASA launched an investigation and paused shuttle flights while it made several key changes to improve shuttle safety. The agency also told the public it would not fix the aging Hubble Space Telescope because if the shuttle broke on the way there, there would be no place for the astronauts to wait for help from Earth.

So how did Feustel find himself fixing Hubble in 2009? Public and scientific outcry made its way to Congress. NASA changed administrators and began looking again at the safety requirements for a repair. The agency is talented at calculating odds and minimizing risk to its astronauts. It found a way to make a Hubble repair work – a scenario where it would have a backup shuttle at the ready to launch should Feustel’s shuttle get stranded in space.

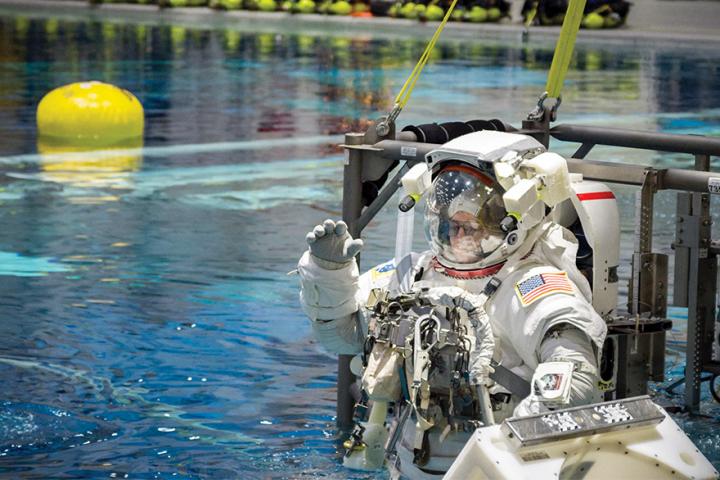

Astronauts are usually too busy with spaceflight training to pay much attention to news events. Feustel was no exception; the rookie astronaut needed to learn how to replace and fix Hubble’s delicate instruments without damaging the telescope, on a mission that would get more public attention than most. That meant long days doing simulated spacewalks in the vast Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory swimming pool, and long nights memorizing procedures to keep himself and his crewmates safe.

“The way we get there is by practice,” he says. “We practise nominal things and off-nominal things. We do those over and over again to build the muscle memory. The things you expect to do are thoughtless.”

This means that if an emergency occurs, astronauts aren’t struggling with what Feustel calls “mental bandwidth.” Like a dance routine, you’ve already memorized the steps if the shuttle begins to go off track during a launch, or if an instrument gets stuck while removing it from Hubble. Instead, Feustel says, when problems happen, you quickly expand your thinking. “I have a problem,” he says, “so what are all the problems I know about? And how can I use that knowledge to create solutions?”

The tactic came in handy when during the fourth of five long Hubble spacewalks, a screw got stripped during removal. Spacewalker Mike Massimino called back to Earth when he realized he couldn’t get a handrail off the telescope as panned. About half an hour later, Feustel recalls, NASA called up with an unexpected solution: since no other astronauts needed to repair this telescope, just break the handrail off. The fix worked beautifully, and before long, Hubble was set on its way to take more cosmic photographs .

Feustel’s next spaceflight in 2011 also got more media attention than usual when his mission commander – Mark Kelly – experienced a personal tragedy. On January 8, Kelly’s wife, former U.S. Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, was badly injured during an assassination attempt. Giffords survived – but she emerged from the incident in need of constant care as she relearned how to walk and speak. Kelly was just four months away from commanding STS-134. NASA and Kelly briefly considered moving him from the mission, but as Giffords recovered, everyone agreed Kelly could go. A special team of hospital workers flew Giffords to the launch in Florida on May 16, 2011 so she could see her husband fly to space.

“In terms of the mission, there were a lot of distractions,” Feustel says now, adding that even with the crew training and commitment they found it “difficult to compartmentalize” after the traumatic event affecting their commander. While he was a junior member of the team on that mission, Feustel came to realize that a mission commander can only control so much of what happens during the training and on a spaceflight himself. It was a lesson Feustel says helped him when he took command of the ISS a few years later.

The tragedy overshadowed some of the expedition’s work, including its important deliveries to the ISS. One experiment it hauled to space, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer 2, searches for dark matter in space, just as SNOLAb does on Earth. Among his achievements with STS-134, Feustel expanded his spacewalk experience with a successful repair-focused excursion that lasted more than eight hours, making it among the longest spacewalks ever performed.

“I did what I could to minimize the distractions,” Feustel says of that mission. The spaceflight also served as a sobering reminder, he says, that the immense teams of unheralded support personnel may need to work around the clock to make a mission happen when something goes wrong. Feustel’s focus in orbit thus became “trying my best to reduce the load of those folks.” He then plunged into the training cycle anew, working to support other missions as NASA shifted its focus to long-duration stays in space.

Drew Feustel is now 53 years old. It’s an age when you need to take time and effort to make sure your body stays fit, especially when preparing for a long-duration mission on the International Space Station. Astronauts exercise daily in space and follow a rigorous eating, moving, and working routine on Earth to keep mind and body fit.

It’s a necessary focus. Space, simply put, can destroy you without careful attention. Microgravity shrinks bones and muscles. Radiation increases the risk of cancer. Many astronauts experience diminished vision after their time in orbit, which could be related to microgravity or something in the ISS environment. Why this happens is something NASA doesn’t yet quite understand.

NASA once wanted to send people to Mars in the 1980s, but we now know it’s a harder process than was ever imagined. Drew Feustel voluntarily subjected his body to more than six months of weightlessness in 2018. The coup was becoming commander of Expedition 56, but the cost would be 197 days spent away from his family, followed by months more of recuperation.

In space, all astronauts undergo a rigorous set of experiments to see how microgravity affects their health. Before they even leave the Earth, baseline measures are taken of their balance, bone density, and muscle mass. The astronauts do their best to stay fit in space, including spending 90 minutes to two hours nearly every day exercising on a treadmill and a resistive device, both with accommodations for microgravity to stop astronauts from floating away. Then, in the moments after they arrive home, more measurements are taken, allowing doctors to build up a comprehensive recovery plan. The rule of thumb is each day in space requires a day of recovery on Earth, but generally astronauts are able to perform most normal duties in a few weeks and to start driving again within a couple of months.

In post-flight interviews, Feustel had time to recall the successes and challenges of his long stay in space. In nearly 200 days in orbit, the commander enjoyed the chance to speak to dozens of schoolchildren, participate in three more spacewalks, and assist with the arrival and departure of six cargo vehicles bringing needed supplies to the station. He also participated in an educational downlink with Queen’s, connecting by video with students and professors (including Art McDonald) gathered in Grant Hall. He and his crew also helped with more than 350 experiments. Among the new equipment they brought to the ISS was the Cold Atom Lab. This laboratory creates clouds of atoms, called Bose-Einstein condensates (BECs), that are cooled to a mere one ten-billionth of a degree above absolute zero, which is even chillier than the reaches of deep space. Here, scientists can examine atoms in a situation in which they have almost no motion, allowing better study of atom behaviour and characteristics. This was the first time that BECs have been produced in orbit.

BECs are created in atom traps, or frictionless containers made out of magnetic fields or focused lasers. On Earth, when these traps are shut off, gravity pulls on the ultra-cold atoms, so they can only be studied for fractions of a second. The persistent microgravity of the space station allows scientists to observe individual BECs for five to 10 seconds at a time, with the ability to repeat these measurements for up to six hours per day. Like most experiments on the space station, this one is automated, allowing data to be collected remotely while researchers on the ground analyze it and come up with results.

“It’s an amazing experiment,” Feustel says, adding it was also memorable to work on because it was such a challenge to set up on the ISS. But the science will be worth it, he adds, when results begin flowing in a few years’ time. The study of ultracold atoms may lead to improvements in several technologies, including sensors that could help detect dark energy.

The lessons learned from his previous missions echoed in Feustel’s mind in 2018 as he saw events happen far outside of his control. During Expedition 56, a leak was discovered on one of the Soyuz spacecraft attached to the space station, necessitating an emergency plug. The minute hole was fixed with epoxy and gauze; an investigation is ongoing and should reveal the cause sometime this year. Feustel had also barely returned to Earth when the launching Expedition 57 crew experienced an abort en route to the space station. They were forced to the ground by a deformed rocket sensor. The Russians, however, quickly rectified the issue and safely launched the Expedition 58 crew on December 3 – a group that included another Canadian, David Saint-Jacques.

It’s all part of the working life of an astronaut: Practise ’til it’s perfect, minimize the distractions, identify the problems you know, find solutions, and keep building upon the knowledge of previous expeditions.