When the Review announced that its series about Queen’s most unforgettable characters would launch with a recollection of the late Ralfe Clench, readers responded with pleasure -- not surprising, since the man was so well and favourably known during his 39 years on campus. In all his Queen's connections – student, scholar, CFRC volunteer, evangelical streetcar buff, both faculty and staff – he inarguably merited the label “unforgettable.”

Ralfe Johnson Clench, Jr., arrived in September 1954 from Hamilton, Ontario, as an Arts’58 freshman, mathematics scholarship in hand, proceeded to grad school (MSc’60) and enjoyed careers in two very different Queen’s Departments that exposed him to virtually every student on campus. One was Mathematics & Statistics, where he lectured in Calculus (only to students with no prior experience) and drove some faculty colleagues scatty with his idiosyncrasies and lectures on “the idiot-proof method” and “your favourite cute cuddly little x's.”

His other appointment was in the Registrar's Office, where the astute Jean Royce hired him in 1962 to serve variously as Chief Examination Proctor, Convocation Marshall, and timetabler for both exams and lectures.* This complex scheduling he handled masterfully and manually, being something of a human-computer. Even after hours, he remained a campus fixture, living among the students.

When ill health forced his early retirement in 1980, a Kingston radio talk show saluted him by inviting listeners’ anecdotes. The stories from Ralfe’s students, neighbours, colleagues, and fellow grads were so many and so colourful that CKLC added a second show. It’s likely that he listened with some satisfaction, for he was well aware of the ‘campus legend’ label he’d earned.

Ralfe died of his digestive illness at home on August 4, 1993. He had requested no funeral and no memorial service. His Whig-Standard obituary, repeated for eternal Googling by The American Mathematical Monthly, was unusually brief, but eloquent: “Brilliant teacher, a kind and considerate man,” it read. “… Will be fondly remembered by friends and colleagues both far and near.”

It said nothing of his hometown, his accomplished Kingston ex-wife, or his family. He was descended from many generations whose menfolk were named Ralfe Johnson Clench, the first of them a Loyalist Niagara settler, a hero with Butler’s Rangers. The perennial middle name Johnson celebrated his connection to New York’s great Loyalist general, Sir William Johnson, and his Mohawk wife Molly Brant (both with Kingston connections), and later his lawyer-ancestors’ kinship with Chief Joseph Brant’s descendants. There was no physical hint of this U.E.L. ancestry in the large, blond Queen’s man whose chief battles involved tilting at the ivory tower.

If he could have planned his death for the campus’s most beautiful and busy season, he might have, because for Ralfe, timing was everything. Punctuality was a passion. Students who came late to class found the door locked, and the story of his class once locking the door on him has become part of Queen’s lore. He began lecturing on the dot of the hour while deftly disassembling the lock with the tool kit always on his belt. Along with tool pouches for screwdrivers, staplers and paper clips, that belt also carried flashlights and rings of keys that might have herniated a smaller man.

In his passion for conserving heat, controlling light, maximizing storage space, and preventing burglary, Ralfe boarded up all his windows (except a small one on the third floor) and installed elaborate ‘thief traps’ of rope.

Other signs of his eccentricities and compulsions were many and easily visible. His overcoat was specially made like a shoplifter's. He used its sturdy inside pockets as a backup filing system and library, adding such seasonal items as insecticides, lock de-icer and slip-proof crampons. Two radios hung around his neck on a rope, each tuned to a different local station, mostly to double-check the weather. He carried several timepieces, preferred the military precision of the 24-hour clock, and stuck to Eastern Standard Time year-round.

York University professor Paul Herzberg, one of his Arts’58 classmates and, in Ralfe’s highly competitive view of things, his chief rival in mathematics, recalls in a letter to the Review that Ralfe’s way of taking lecture notes caught his attention early. “He always carried a very large black briefcase that contained several clip-boards, on each of which he had clipped a stack of loose-leaf paper with carbons between them. I don’t recall how many copies he made,” Paul writes, “but every few minutes during the lecture, he would complete one sheet in his large handwriting, put the clipboard in his briefcase and pull out the next, all ready for him to keep on writing.“ Neither of us can recall – if we ever did know -- why our classmate thought every word was necessary and in multiple copies.

“One can only imagine the huge pile of notes amassed in even a single term,” Paul concludes. By multiplying his note-making and note-taking habit by the years from ’54 to ’80, one can scarcely imagine the piles of notebooks behind his home’s boarded-up windows and the daunting task of the executors charged with sorting papers after his death.

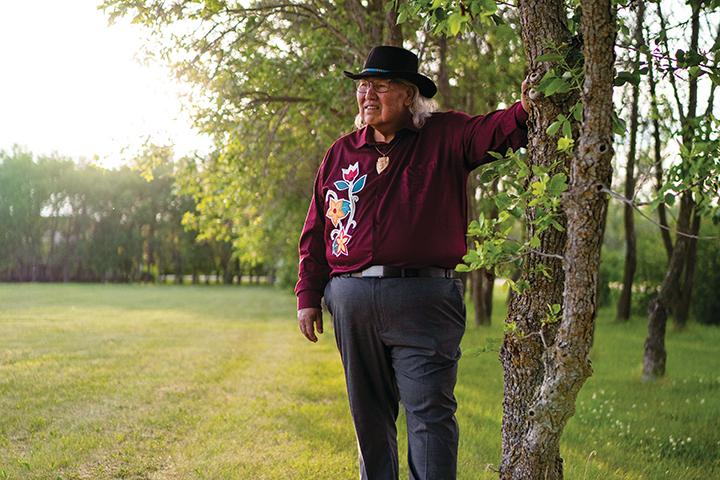

He was a tall man, even as an 18-year-old student, rotund when healthy, and, if all his pockets, tool pouches and both hands were full, he was indeed a broad and striking campus figure.

He ordered his clothes in batches – sometimes, as in the case of underwear and toe rubbers, by the gross. His pants were made-to-order, with reinforced canvas pockets and heavy-duty belt loops. His shoes, too, were specially made for his narrow and unusually long feet. Because resoling such expensive footwear was costly, he wore toe-rubbers in all seasons except deep winter, when he changed to old-style, cleated rubber overshoes. His shirts were always white, as the pants were always gray and baggy, with each item identical to its predecessor. Except for his unbuttoned winter buffalo coat, the spring and fall coats were always beige. Every piece was assigned a schedule of wear, and despite oft-turned collars and much-mended cuffs, nothing was discarded before its due date.

Ralfe's sociable perambulations from home to his two offices and the College Variety store had another trademark: plastic shopping bags that had supplanted the huge and once-ubiquitous black briefcase. Usually, they were Dominion Store bags; invariably they were carried by admirers from his classes or co-workers worried about his health. What was in those bags? Mostly duplicates of every document handled in his daily work. When his executors began the mammoth job of sorting his hoarded 'treasures,' some of these papers were offered back to Queen's. The fact that some of them helped fill archival gaps would have pleased Ralfe greatly.

Both of his near-campus homes -- first on University Ave., where he sometimes proctored special exams, and then his brick ‘fortress’ at the corner of Frontenac and Union Streets -- had complete office set-ups. In his passion for conserving heat, controlling light, maximizing storage space, and preventing burglary, Ralfe boarded up all his windows (except a small one on the third floor) and installed elaborate ‘thief traps’ of rope. Yet he was no hermit; he spent a lot of time leaning on his cane and visiting with passersby while outdoors checking his 'perimeter.'

His calculus students held him in such high regard that he was among the first nominees when the Alumni Association instituted its $5,000 Award for Excellence in Teaching. Though his part-time status made him ineligible, his enthusiastic students doggedly nominated him every year till he retired.

Ralfe was 58 when he died, but he seemed visually unchanged all those Queen’s years because of the same Oliver Hardy moustache, the hair clipped high above the ears, the hat-for-all seasons, and the identical wardrobe year in, year out. The one-and-only Ralfe Clench will live for many more years wherever tales of Queen's characters are told, right up there with an earlier generation's Dollar Bill, Alfie Pierce, and “Miss A,” Margaret Austin.

*Paul Herzberg, Arts’58, calls attention to Jean Royce’s glowing tribute to Ralfe’s work for her in the Roberta Hamilton biography entitled Setting the Agenda: Jean Royce and the Shaping of Queen’s University (U of T Press 2002).